Polyphonic Philosophy

Investigating Logical Commentaries from the Long Twelfth Century (c. 1070-1220)

Project

Welcome to the website “Polyphonic Philosophy: Logic in the Long Twelfth Century (c. 1070-1220) for a New Horizon in the History of Philosophy”.

The project aims at an interdisciplinary, manuscript-based approach to Latin logical commentaries from the Long Twelfth-Century (c. 1070-1220).

The contention behind the project is that this little-explored topic presents us with a unique “polyphonic philosophy” that can open up a new horizon in our understanding of philosophical commentaries, on the one hand, and help to reshape some core ideas in the history of philosophy, on the other.

Histories of philosophy often tend to consider philosophy as a solo enterprise: the achievement of exceptionally gifted philosophers, reached by means of their individual intellectual powers alone. However, for more than fifteen centuries in the West (from c. 50 BCE to c. 1600 CE), a different “style” of philosophy was also widespread in the whole Mediterranean area, namely, philosophical commentaries. Commentaries are an intrinsically collective enterprise, in which many voices harmonise: the authoritative text to be commented on, the pre-existing tradition of analysis, the commentator’s own discussion.

In this project, we will focus specifically on commentaries dating from c. 1070 to c. 1220, the so-called “Long Twelfth Century”. This is a very special time in the history of education and of books. It has been described (Rexroth 2018) as a period of “joyful scholasticism”, in which various educational communities and various forms of teaching emerged. From these, European universities would develop, as would – as Richard Southern famously argued (1995, 2001) – a unity of culture across Europe. One of the key aspects of this development was, precisely, a new method of textual analysis in the form of commentaries. But equally important were the interplay between orality, aurality, and written culture in this context; the growth of the teacher’s fame; and the personal and emotional ties linking teachers and their pupils.

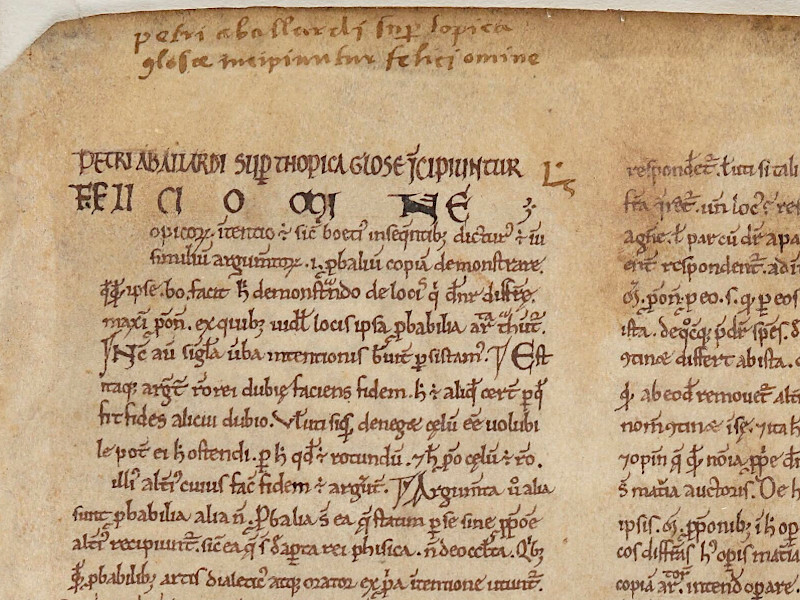

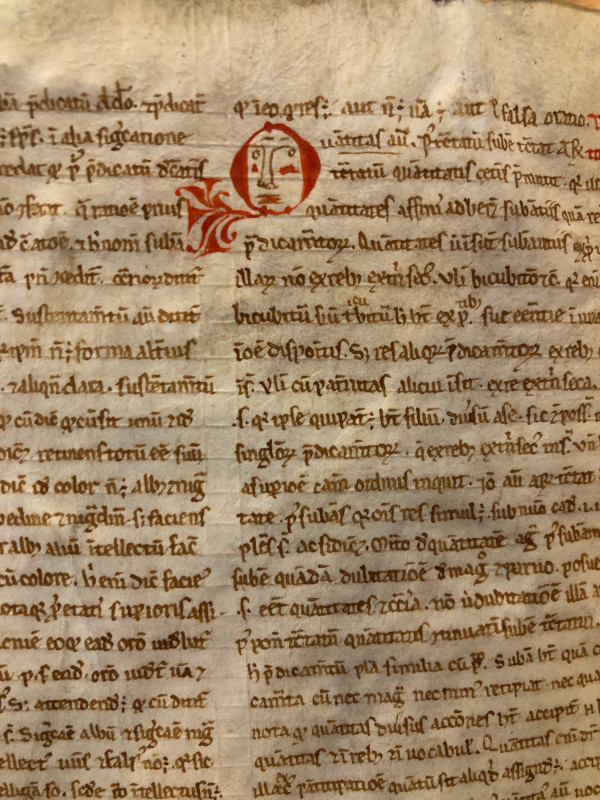

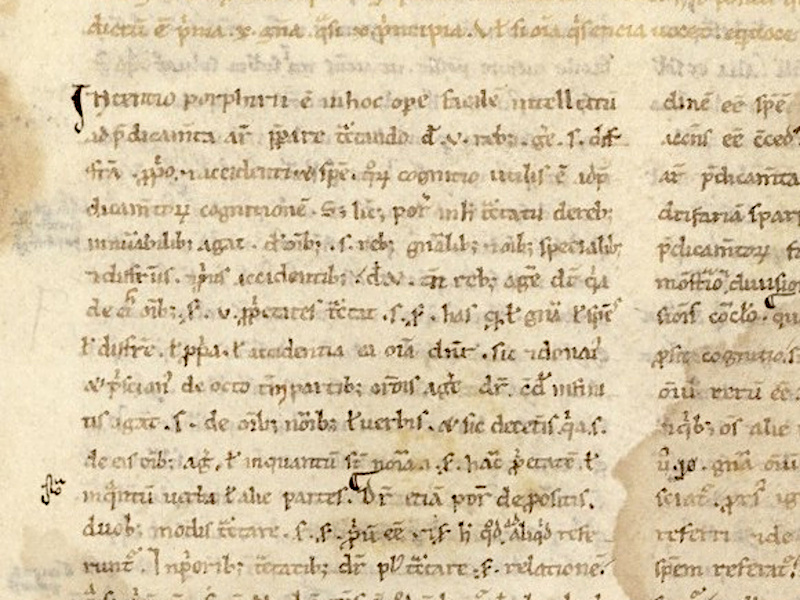

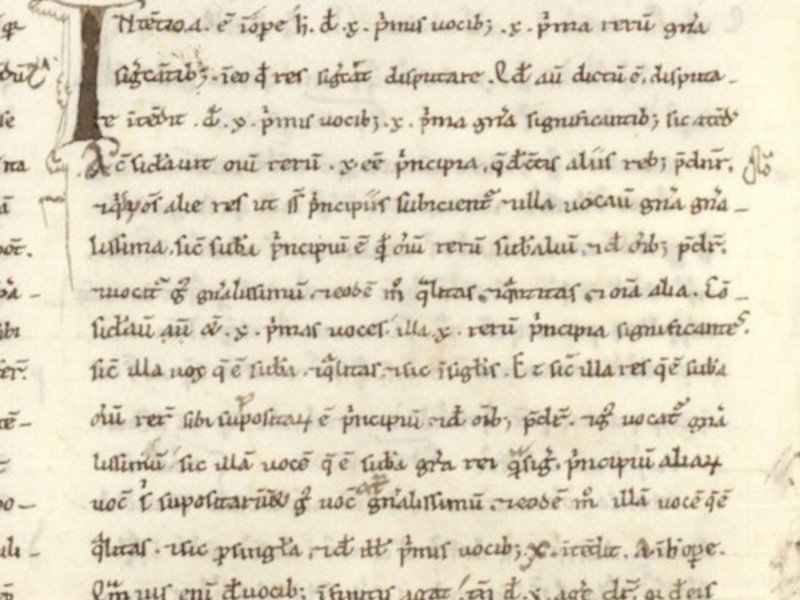

In the field of logic (or dialectics), important new features emerge in the Long Twelfth Century, which mark it out from previous and subsequent times. Extensive commentaries start to be written on ancient and late ancient texts by Aristotle, Porphyry, Priscian, and Boethius which (though technically available in the High Middle Ages) had not been the object of such in-depth study before.

Important preliminary research by Yukio Iwakuma and John Marenbon enabled them to catalogue more than 200 logical commentaries of varying length, many of which are still unpublished. Preliminary transcriptions show that many new ideas were tried out by commentators, and their analysis became very sophisticated.

These logical commentaries had a direct influence on the remarkable development of logic later on in the Middle Ages.

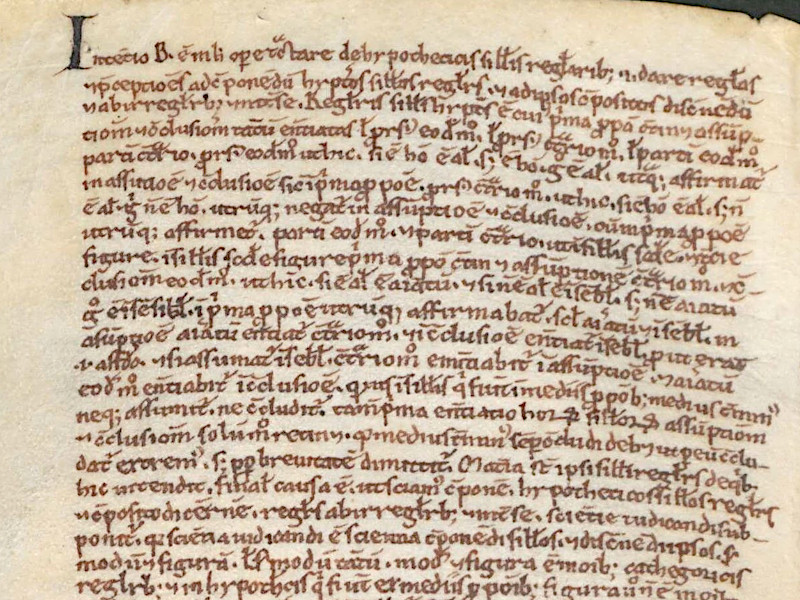

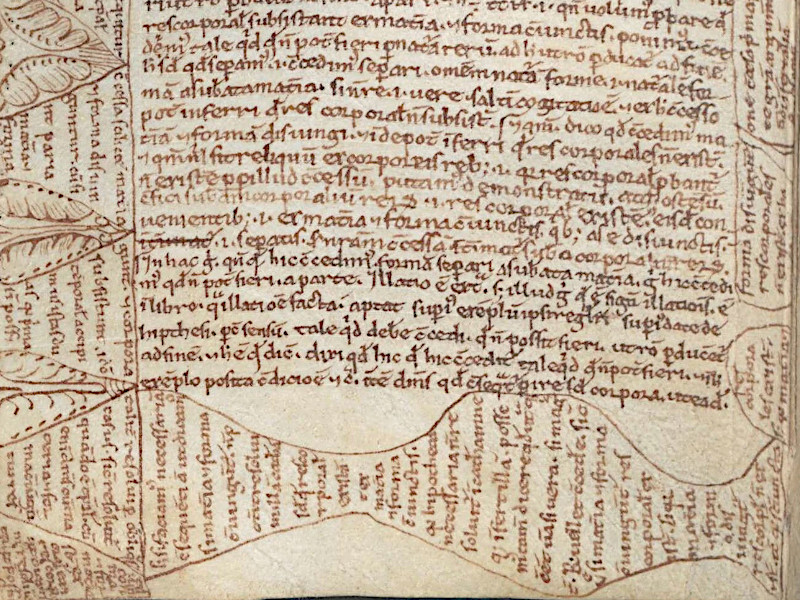

But not only are texts remarkable: the manuscripts in which these texts are found also have some unique features. Twelfth-century logical commentaries quickly became surpassed by later development and were virtually neglected after around 1220. So, they circulated in very few codices (most texts are single-copy; and the entire production is contained within only around 40 manuscripts overall), which all date from the twelfth century itself. This seemingly unfortunate situation and paucity, however, turns out to be a special richness for today’s researchers.

These manuscripts enable us to immerse ourselves immediately in the time and context in which the texts were written down. Through these tiny, unadorned books, probably belonging to commentators themselves, or to their students, one can have a direct glimpse, so to speak, into the practices and schools from which 12th-century logical commentaries stem.

The analysis of these manuscripts is therefore the basis for the whole development of the project, which follows a concrete-to-abstract integrated research design.

Objectives and methods

We will follow three intersecting lines of research:

- Objective 1: a comprehensive study of 12th-century logical manuscripts as the main units for accessing this complex field, in which the notions of unitary text and author have proven challenging.

- Objective 2: a study of mainly unpublished logical texts following a comparative approach across them all; we will also develop some scholarly editions of texts to model their “polyphony” in the digital sphere.

- Objective 3: a meta-analysis of the concepts used from an interdisciplinary and historiographical perspective, offering new insights into the key concepts of the project, and non-solo paradigms to reconstruct philosophy’s past.

The project requires a combination of expertise, including digital medieval studies, textual criticism, codicology, paleography, the history of education, the history of literacy, the social history of logic, the history of philosophy, and the historiography of philosophy.