Shida Kartli

Georgian-Italian Shida Kartli Archaeological Project (GISKAP)

The “Georgian-Italian Shida Kartli Archaeological project” of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in collaboration with the Georgian National Museum di Tbilisi is active since 2009. It is coordinated by Elena Rova for the Italian side, by Zurab Makharadze and Marna Puturidze (2009-2012) and Iulon Gagoshidze (2013-) for the Georgian side. It deals with the pre- and proto-historic cultures of the Shida Kartli region, the core of Georgia, the mythical "land of the Golden Fleece", in the Southern Caucasus, a land of ancient wine growers, skilled metallurgists and stockbreeders. The chronological scope of the project extends from the Late Chalcolithic to the Iron Age (4th-1st mill. BC). Georgian and Italian researchers and students, as well as international experts, take part in the yearly field seasons.

The projec’s perspective is regional, that is, not centered on the single site, but on the relations between different types of sites (large and small settlements, cemeteries etc.), for a reconstruction, in a diacronic perspective, of the changing relations between the human groups and their natural environment, and ont he connections between the local populations and their suthern neighbours, the urban civilisations of the Near East. The approach is multi- and interdisciplinary, with the active participation of the experts in different disciplines to the field seasons. A primary task is the establishment of a reliable relative and absolute regional chronology for the Shida Kartli region.

As yet excavated sites are Natsargora, Okherakhevi, Aradetis Orgora and Doghlauri. Excavation is joined by the study of artefacts from local museums (Natsargora settlement and cemetery, Doghlauri cemetery) and by palaeoenvironmental and archaeometric research.

In the course of the first seasons attention especially focused on the Early Bronze Age Cultures (Kura-Araxes and Bedeni) both as far as settlements and, especially, as fara as burial customs are concerned. The Aradetis Orgora site, however, yielded a nearly complete stratigraphical sequence from the end of the 4th to the mid 1st millennium BC, with important results on the Middle Bronze (first half of the 2nd) and LateBronze/Early Iron Age (second half of the 2nd/1st half of the 1st millennium BC).

Sites

Sites

Aradetis Orgora

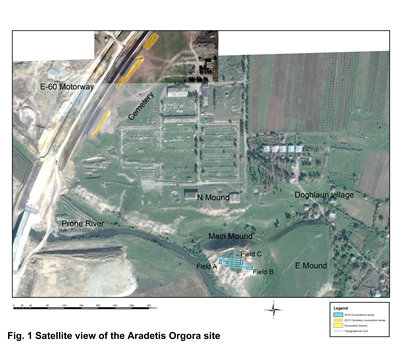

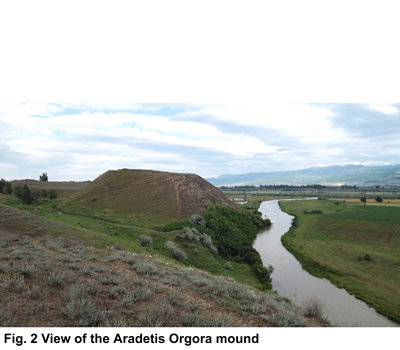

Aradetis Orgora in the Kareli district (42°02’48” N, 43°51’37” E) is one of the most important archaeological site in the Shida Kartli province, and probably represented a regional centre over most of its history. The site occupies a highly strategic position on what was, and still is, one of the main communication routes in the South Caucasus, presently corresponding to the line of the modern highway crossing Georgia in the east–west direction. Located at the southern edge of the gently sloping Dedoplis Mindori plain, at the confluence of the Western Prone River and the Kura, it dominated the river plain and had easy access to the fertile soil of the adjoining terraces. The archaeological area extends over a maximal surface of c. 40 ha and includes three different mounds (the Main Mound, also known as Dedoplis Gora “the Queen’s hill”, the Northern Mound and the Eastern Mound) and a wide burial area (Doghlauri cemetery) (Fig. 1). It was the object of sporadic human frequentation since the Paleolithic period, and continually occupied from the Late Prehistory to the Early Middle Age.

Excavations, since 2013, by the Georgian-Italian Shida Kartli Archaeological expedition focused on the Dedoplis Gora mound, a 34 m high steep-sided hill of triangular shape that dominates the Kura valley (Fig. 2). The total depth of archaeological levels measures at least 14 meters, and consists of an almost continue sequence from the Late Chalcolithic (4th millennium BC) to the Early Middle Age (6th century AD) periods.

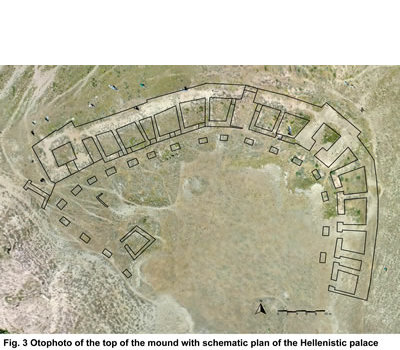

The site is presently dominated by an impressive fortified palatial building of the Late Hellenistic–Early Roman period, which probably originally occupied the whole hilltop surface (more than 3000 m2) and, due to its remarkable preservation, represents a unique example of monumental architecture of the period (Fig. 3). Founded at the end of the 2nd or in the early 1st century BC and destroyed by an earthquake and intense fire around 80 AD, the palace at Dedoplis Gora was probably the residence of a local vassal of the king of Kartli (Caucasian Iberia), responsible for administering the royal domain in Shida Kartli. It had an irregular triangular shape, and was provided with massive corner towers of squared shape. Surrounded by an almost 3 m-wide outer wall, in which – on the ground floor at least – no windows were found, it consists of a row of rooms which open onto a large central peristyle court. The building originally had at least two storeys and was covered by a tiled roof. The rooms of the ground floor were mainly devoted to everyday activities and to the storage of less precious wares. Residential units were probably located on the upper floor(s), where luxury goods were also kept, while the central court and the peristyle were occupied by less monumental structures, mainly devoted to processing agricultural products.

The building had previously been investigated by a Georgian team headed by Iulon Gagoshidze (1985-2007). Since 2013, excavations were resumed in the framework of the Georgian-Italian Shida Kartli Archaeological project. During the 2013-2015 seasons, three new rooms and the corresponding portion of the pillared portico were excavated (Fig. 5). A complete, undamaged fire altar was discovered in one of these rooms, on the surface of which lay a votive deposit including bronze and silver divine figurines of, among others, Apollo, Leto, and Tyche-Fortuna, along with a silver censer, a gold ivy (?) branch, two pheasant's eggs, and a total of 15 coins (Fig. 6). From the ruins of the palace, samples have been taken for palaeoenvironmental analyses, together with samples of building materials. A team of specialists produced a preliminary report of the building's present state of preservation, with the aim of developing an overall plan for its future preservation and promotion.

The over ten metres of pre-Classical occupation of Dedoplis Orgora had never been explored before the beginning of the joint Georgian-Italian project. The two deep soundings opened in the opposite sides of the hill have confirmed that the most important occupation phases of the site correspond to the Kura-Araxes Period (second half of the 4th-first half of the 3rd millennium BC), with a 4 meters high occupational sequence (Fig. 7), and to the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Periods (15th-7th centuries BC), which apparently correspond to the main phases of use of the neighbouring cemetery area. Less intensive occupation (mainly in form of sporadic material) was observed for the later Early Bronze period (Bedeni culture), while, for the first time in the Shida Kartli region, evidence for the presence of Middle Bronze Age layers (first half of the 2nd millennium BC) has been brought to light. There are also indications that the main construction episodes (re-shaping of the mound's outer limit during the Late Bronze period, erection of the Hellenistic palace) may have almost completely obliterated some of the underlying levels.

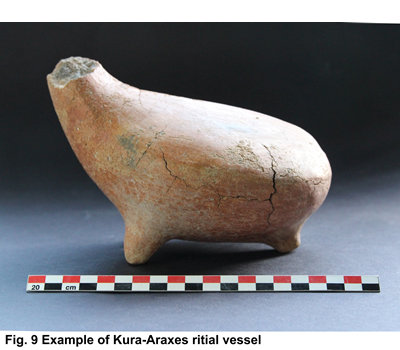

The importance of the site during the Kura-Araxes period is confirmed by the discovery, in the Eastern Sounding, of different types of architectural units (round-shaped huts with clay walls, wattle-and-daub rectilinear structures). Especially noteworthy among them is a portion of a possibly cultic building, (Fig. 8) from the floor of which came a group of ritual vessels with zoomorphic/anthropomorphic features (Fig. 9). The presence in the Kareli and Gori districts of a number of contemporary sites with similar features, located at regular distances from each other in the valley of the Kura River and along the courses of its main tributaries, proves that Aradetis Orgora was not an isolated case and shows that this part of the Shida Kartli region was a focus for stable and relatively intense occupation during the Kura-Araxes period.

Evidence from both soundings fields proved that during the Late Bronze and the Iron Age Periods the slopes of the Dedoplis Gora mound underwent repeated episodes of re-shaping, consisting of the erection along its perimeter of massive stone walls (partially lost because of erosion), the space inside which was filled with alternating layers of river pebbles and compacted clay. Rather than being parts of a fortification system, these stone walls appear to be retaining walls, probably belonging to an extensive terracing system aimed at consolidating the mound's slope in order to create new space for the settlement, whose population was progressively growing, as also suggested by the contemporary expansion of the settlement onto the Northern and Eastern Mounds, as well as by the large number of contemporary graves discovered in the cemetery. During these phases, the excavated areas located at the periphery of the Main Mound were mainly occupied by open-air spaces, which yielded, among others, interesting examples of different types of firing installations (Fig. 10).

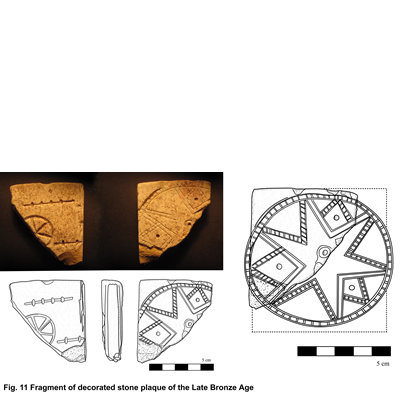

Indeed, this period was characterised by a re-settlement of the territory by a network of permanent sites and by the progressive development of structured political entities, which interacted in a increasing way with the Near-Eastern empires. The recovery, albeit in secondary contexts, of a number of significant finds from the Late Bronze and Iron Age levels (Figs. 11, 12, 13) further confirms the site's affluence during these periods and represents evidence for its regional importance and far-reaching connections.

Natsargora

The site of Natsargora (42°04’13” N, 43°42’54” E) lies in the Khashuri district, at the western limit of the Shida Kartli province (Fig. 1). It is located near the present village of the same name, in the hilly area to the north of the Kura River valley, at ca. 750 m a.s.l. Excavations at the site were carried out between 1984 and 1992 by the Khashuri Archaeological Expedition headed by the late Alexander Ramishvili. In 2009-2010, the "Georgian-Italian Shida Kartli Archaeological Project" carried out the study of the unpublished Early Bronze Age finds discovered by the Georgian expeditions; in 2011 and 2012 the joint Georgian-Italian team carried out two seasons of excavation at the settlement mound (Fig. 2).

The site consists of a small multi-period mound and of a neighbouring cemetery. The mound is 20-25 m high, oval in shape, and measures ca. 90 x 50 m It was occupied during the Early Bronze Age (3rd millennium BC), and the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age (second half of the 2nd and first half of the 1st millennium BC). The cemetery is located in the flat area to the south-east of the mound, and was in use, with interruptions, from the Early Bronze until the Classical Antiquity period. Out of ca. 500 excavated graves, 26 were EBA in date.

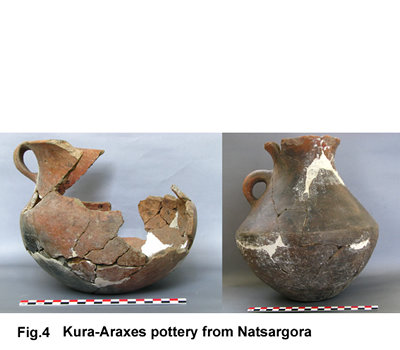

The settlement was founded at the end of the 4th mill. BC, during the second phase of the Kura-Araxes culture. The village consisted of circular huts (Fig. 3) and wide areas provided with fire installations of different types. Although architectural remains were rather ephemeral, the Natsargora population was basically sedentary, even if part of probably practiced a kind of seasonal transhumance towards the mountain pastures. Paleobotanical and archaeozoological and analyses confirmed that the ancient population of Natsargora practiced cereal agriculture (especially of wheat and barley) integrated by animal husbandry (ovine, bovine/cattle and swine are all attested) and by the hunt of wild animals. Craftwork activities were carried out in a household, domestic context. They include first of all the production of the typical Kura-Araxes pottery (Fig. 4), characterised by burnished surfaces of red/black colour, but also metallurgy, as testified by the discovery of small crucibles and by the occurrence of metal objects in the burials of the contemporary cemetery.

The Kura-Araxes burials of the Natsargora cemetery are simple pits covered by stones, that usually contain one adult individual lying in foetal position on one side with the hands placed in front of the face (Fig. 5). Gravegoods usually consist of few pottery vessels, personal ornaments – metal pins, bracelets and hair-rings (Fig. 6), necklaces made of metal, stone and paste beads – and other artifacts of stone, bone or metal. A few double, and one multiple grave are also attested. The finds from the graves mirror a basically egalitarian social organisation, in which differences of status, gender etc. are apparently not stressed.

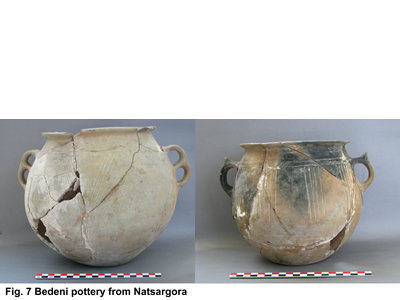

The Kura-Araxes village was inhabited for a maximum of 100-150 years, before being temporarily abandoned. The re-occupation of the site, around the mid-3rd millennium BC, was related to the Bedeni culture, whose people practiced a more mobile lifestyle, probably focusing on cattle breeding. No graves were found for this phase, which on the settlement was almost exclusively represented by pits. These contained large amounts of high quality pottery, often characterised by very elaborate shapes and decorated with incisions, which was probably used during banquets and ritual occasions (Fig. 7). Several fragments of terracotta cultic reliefs representing beings with a vaguely anthropomorphic appearance and large eyes inlaid with obsidian flakes (Fig. 8) were recovered in the levels of the same phase, which confirm that the site during this period was the seat of cultic activities.

There followed, at the end of the Early Bronze Age, a longer period of abandonment of the site, which resulted into the sealing of the EBA layers by an up to 50 cm layer of sterile soil, before the establishing there, at the beginning of the LBA, of a new sedentary village. This had been excavated by the Georgian expedition in the 1980-90ies, and little of it remained when new the new Georgian-Italian excavations were started in 2011.

Okherakhevi

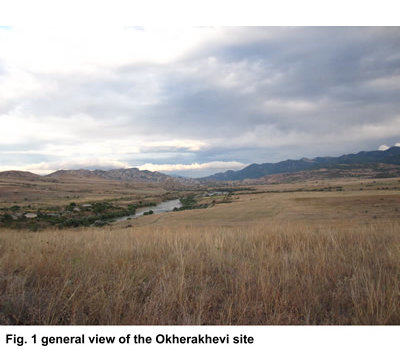

Okherakhevi (41°52’13” N, 44°31’23” E) is situated at the eastern border of the Shida Kartli province, at the border between the Kaspi and Mtskheta districts, between the villages of Nichbisi and Kvemo Khandaki. The site lies at an altitude of ca. 510 m a.s.l, on a flat area on the lower terrace of the Kura River located ca. fifteen meters above the present course of the latter (Fig. 1), at a distance of about 4.5 km in south-eastern direction from the Early Bronze Age settlement of Tsikhiagora, and ca. 1.6 km to the South of the Late Bronze site of Kvemo Khandakis Gora. The area was used as a burial field from the mid-3rd millennium BC to the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. Burials belong to the so-called kurgans (monumental funerary barrows belonging to tribal chiefs). Such burials, which required a huge work investment in the mound building and were often provided of very rich grave goods, testify the emergence in the region of a stratified society.

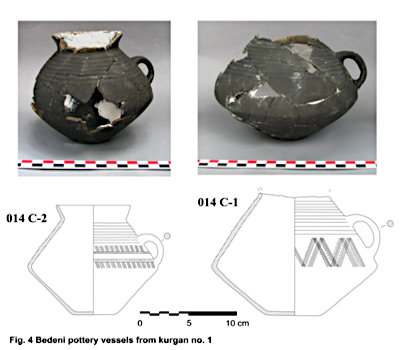

During the 2010 field season, the Georgian-Italian team excavated two kurgans at Okherakhevi. Kurgan no. 1, of the Early Bronze Age (Bedeni culture), measured 10 x 4.50 m, and had a maximum height of 70 cm. It had the shape of an elongated oval, oriented in NW-SE direction (Fig. 2). The kurgan’s mound consisted of rounded and smooth pebbles and of larger slabs of whitish-greyish and yellowish sandstone. Numerous flakes of unworked obsidian were recovered from among the kurgan’s stones. A low overground chamber of squarish shape, oriented in NW-SE direction, was located approximately in the centre of the stone mound (Fig. 3). It contained a few badly preserved tiny fragments of human bones and two pottery vessels of Bedeni Fine ware (Fig. 4).

Kurgan no. 2 was attributed to the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age. Its stone mound was 20-50 cm high, and measured 15 x 11 m (Fig. 5) It was composed for the most part of river pebbles of greyish colour, similar to those of kurgan no. 1, but generally of smaller size; a dozen fragments of obsidian and two fragments of red flint were recovered in-between the stones. A large 1.5 m deep pit of irregular hemispherical shape filled with different layers of stones was found in the central part of the stone mound (Fig. 6). Except for some small fragments of decomposed animal bones, nothing was found in the pit’s filling. Two small pits which cut the main one contained fragments of small-sized pottery vessels of the Late Bronze Age period. A third Late Bronze Age pit located at the NW periphery of the kurgan contained two smashed pottery jars with very typical Late Bronze Age combed/impressed decoration and scattered animal bones (Fig. 7).