Physiognomics as Philosophy

Reconceiving an Early Modern Science

Project

"There’s no art/ To find the mind’s construction in the face"

declares King Duncan in Shakespeare’s "Macbeth".

According to early modern experts on physiognomics, Duncan was tragically mistaken.

The philosophical ‘art’ of physiognomics demanded refined theoretical and practical skills, including knowledge of human nature, anatomy, and medicine. Its ideal practitioner cultivated refined aesthetic judgment and rhetorical skills.

It was believed invaluable in politics as it enabled allies to be distinguished from enemies.

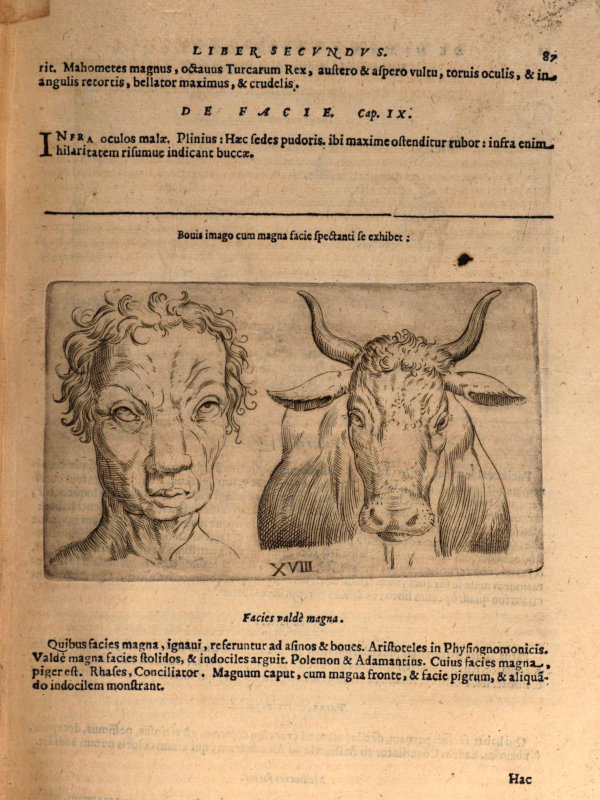

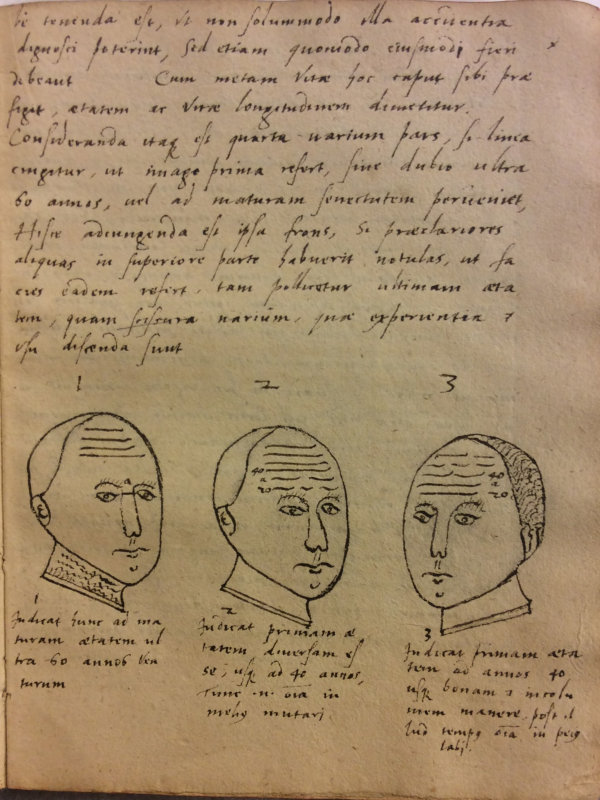

Physiognomics is the theory that there is a direct correlation between the inside and the outside of a living being, between body and soul: for instance, a large forehead, resembling a bovine head, was supposed to indicate foolishness [Fig. 1].

In antiquity, important physiognomic treatises were attributed to Aristotle, Polemon, and Adamantius among others; the Physiognomonica that circulated under Aristotle’s name, and which was translated into Latin by Bartolomeo da Messina (13th century) was particularly influential.

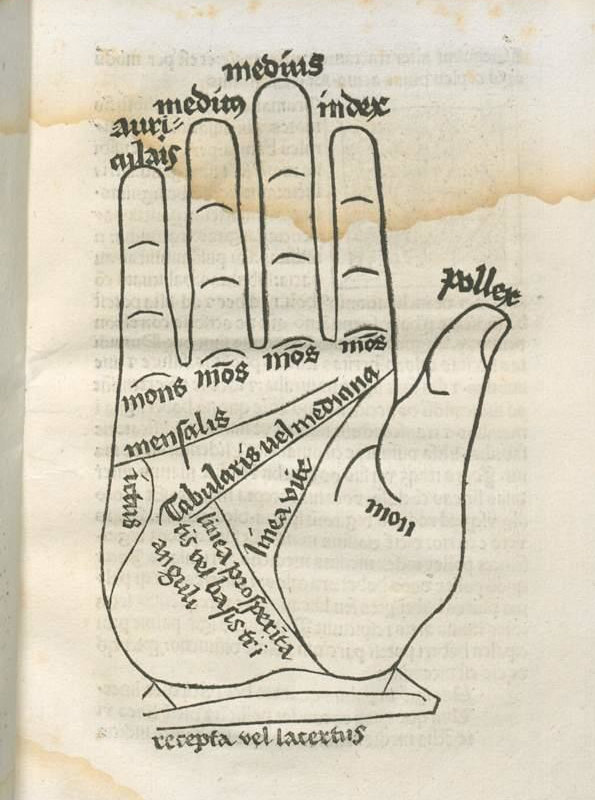

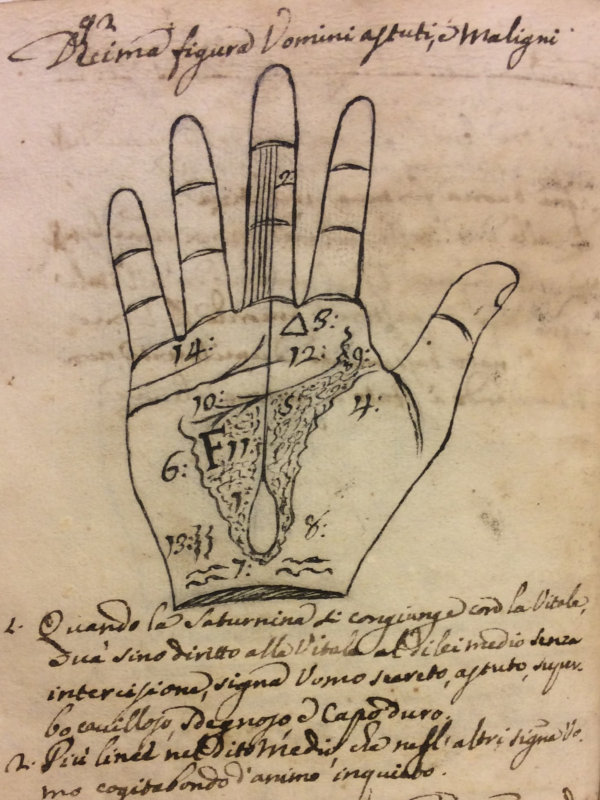

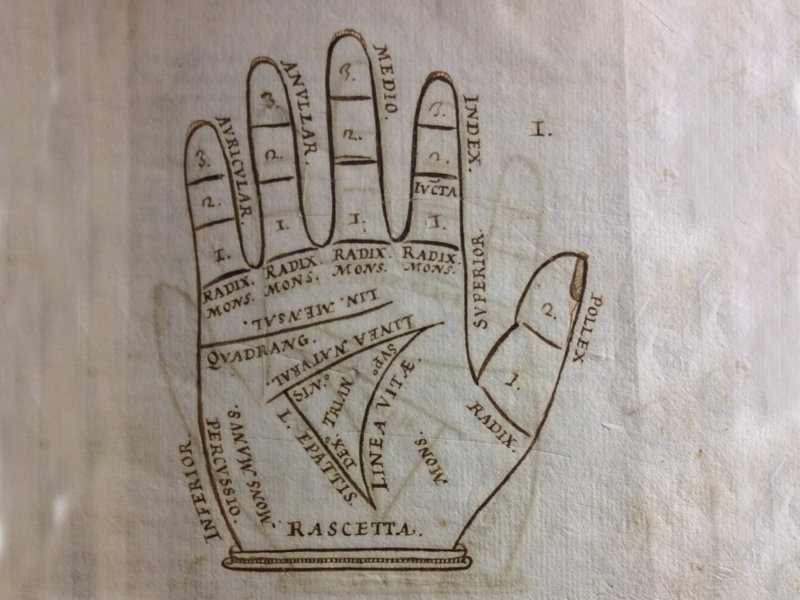

Chiromantic texts – that is to say texts dealing with the physiognomic reading of the hand – were often also placed under the authority of Aristotle [Fig. 2].

Ancient approaches provided impulses for medieval and early modern re-elaborations, and the discipline flourished from the end of the 15th to the mid 17th century, with hundreds of publications in several European languages and a significant manuscript circulation.

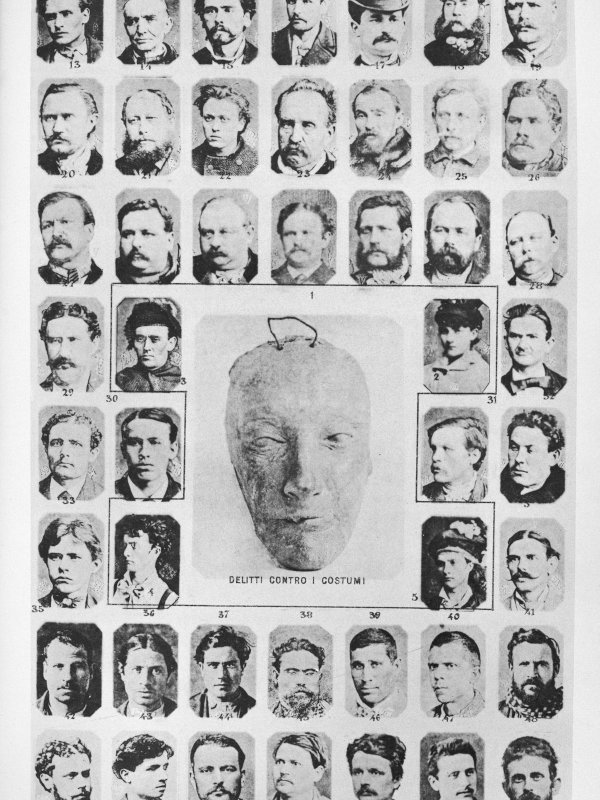

Yet 18th- and 19th-century developments led to the establishment of the very partial view that physiognomics was a deterministic approach connected with the emerging theories of race and of criminality.

This is exemplified by Cesare Lombroso’s theory that delinquent human beings share certain physical characteristics [Fig. 3].

In this process, the important philosophical contributions of physiognomics were lost, giving way to the narrative that physiognomic theories paved the way for racism and even fascism.

Yet, in early modernity physiognomics was an important branch of philosophical enquiry. One of the leading experts of the discipline, Giovan Battista Della Porta (1535-1615), regarded it as synonymous with philosophy itself.

This project reveals the reasons for physiognomics’ forgotten centrality to early modern philosophy. Having defined the corpus of early modern physiognomic works, it will analyse this literature in terms of three contested borders:

- the intersections of science and magic;

- definitions of the human being as a special animal;

- concepts of the difference between mind and body.

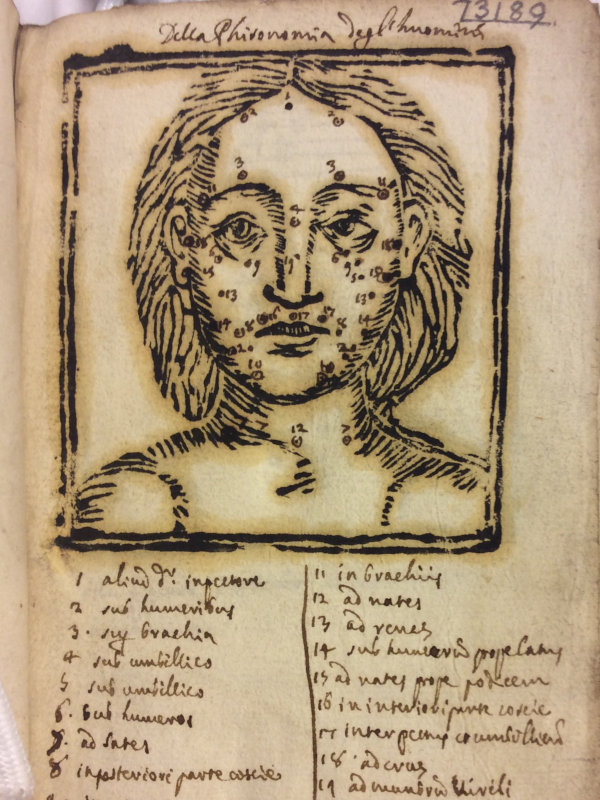

The study of physiognomics provides a new vantage point to reconsider these three areas of early modern philosophical debate, drawing on neglected sources, including several manuscripts.

The project also explores new theoretical connections between historical and contemporary discussions of human representations.

All photographs of manuscripts from the Wellcome Collection are by Cecilia Muratori, who is grateful to the Wellcome Trust for generous permission to use them for this website.

Sources

A series of key sources on physiognomics are made available in English translation in this section.

The aim is to showcase the variety of early modern physiognomic approaches, and to highlight some relevant conceptual shifts.

All translations are by Cecilia Muratori if not stated otherwise.

|

|

Camillo Baldi | 378 KB |

|

|

Girolamo Cardano | 701 KB |

|

|

Thaddaeus Hagecius | 447 KB |

Multimedia

Physiognomics in the Wellcome Collection: Danny Rees in Conversation with Cecilia Muratori

The Wellcome Library in London holds one of the largest and most important collections of physiognomic prints, manuscripts and objects, from antiquity to the contemporary world. In this video, Daniel Rees (Engagement Officer, Wellcome Collection) discusses the intricate history of physiognomics with Dr Cecilia Muratori (Marie Curie Fellow, Ca' Foscari Università di Venezia), showing that this discipline has had a remarkable impact on fields as different as medicine, photography, ethics, fashion, divination, and even contemporary politics.

Events

Past events

28/05/2021 - Cecilia Muratori (Università Ca' Foscari, Venice): 'A "Mirror for Promoting Good Behaviour": Physiognomics as Ethical Practice'. With a response by Valentina Lepri (Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw)

from conference Reading the Virtues: Literary Culture and the Good Life in Europe, 1450-1750.

Physiognomics is often viewed as a deterministic discipline which claims to be able to understand a person’s character by reading bodily signs. As such, physiognomics has been lately accused of being intrinsically racist, paving the way for fascist ideologies.

Yet, in the Renaissance physiognomics was recognised as a branch of philosophy which focuses on the varied interactions of the body and the soul, not only giving instruments to the practitioner to recognize certain character traits by examining bodily features, but also providing information on how to intervene on the body in order to trigger certain changes at the level of the soul.

The thesis of this paper is that as such physiognomics was inherently rooted in ethical reflection. I will analyse physiognomics’ bearing on ethics by emphasising the varied genres in which physiognomic reflections were presented, ranging from large treatises (such as Della Porta’s) to short manuals intended for a broad audience, which were often made available in multiple languages on the European market.