MEDLUNI

Vernacular Literature and Medieval Universities

The Birth of a New Transnational Literary Identity (France and Italy, 1220-1399)

Project

MEDLUNI investigates how – between 1220 and 1399 – the newly born universities shaped vernacular literature in Western Europe, representing a cradle for transnational literary cultures. The research focuses on this osmotic process, occurred in 180 years, starting with the birth and growth of universities and ending when the medieval academic model and scholasticism collapsed. The actors involved in this literary transformation are French and Italian personalities being – at the same time – deeply linked to universities, as ‘magistri’ or ‘scholares’, and authors of literary texts in vernacular languages.

Thus, the research aims at:

- identifying which authors and texts prove the emergence of a new local literary identity linked to the birth of universities;

- recognising which literary features were imported from university texts and disciplines;

- determining how texts, manuscripts, and actors circulated across Italy and France, shaping new literary networks among universities and municipalities.

Descriptors: Romance Philology, Codicology, Stylistics, Cultural Studies, Urban literature, Medieval Universities, Transnational History, Cultural Migrations

Publications and events

Participation to conferences and seminars

- 23-24 January 2026 - Sorbonne Université, France

"Érôs au Moyen Âge. Hommage à Charles Baladier". Conference organised by François Trémolières and Jean-René Valette, with the support of EA EETM, ED 022 Mondes anciens et médiévaux (Sorbonne Université) and CELLAM (Université Rennes 2). Within the MEDLUNI project, Valeria Russo will present the paper «Visions de la faute (à partir de l’érôs)» - 2 July 2025 - XXXI International Congress of Romance Linguistics and Philology - CILFR 2025 [ITA], University of Salento, Italy

Valeria Russo will present the paper «Riflessi della cultura universitaria in un codice miscellaneo. I Salmi penitenziali in volgare nel ms. Paris, BnF, fr. 1109» within the MEDLUNI project at the CILFR 2025. - 21 May 2025 - University of Fribourg, Switzerland

Valeria Russo will present MEDLUNI at the Colloque de recherche en langue et littérature médiévales, organised by Marion Uhlig at the Department of French, Université de Fribourg. - 10 May 2025 - International Congress on Medieval Studies, Kalamazoo, USA

Valeria Russo will present her project MEDLUNI at the 2025 International Congress on Medieval Studies. Her paper, «Scholarly Knowledge in Urban Contexts: Prayers and Classics in Vernacular Codices Miscellanearum (1220-1399)», explores the coexistence of devotional and classical texts in scholastic and academic manuscripts. - 7 May 2025 - University of Notre Dame, USA

As part of her ongoing research within the MEDLUNI project, Valeria Russo will present the paper «Le sage et la page: mise en livre de textes profanes dans les milieux universitaires» at the seminar What Comes after the “New Philology”? (University of Notre Dame).

Organised events

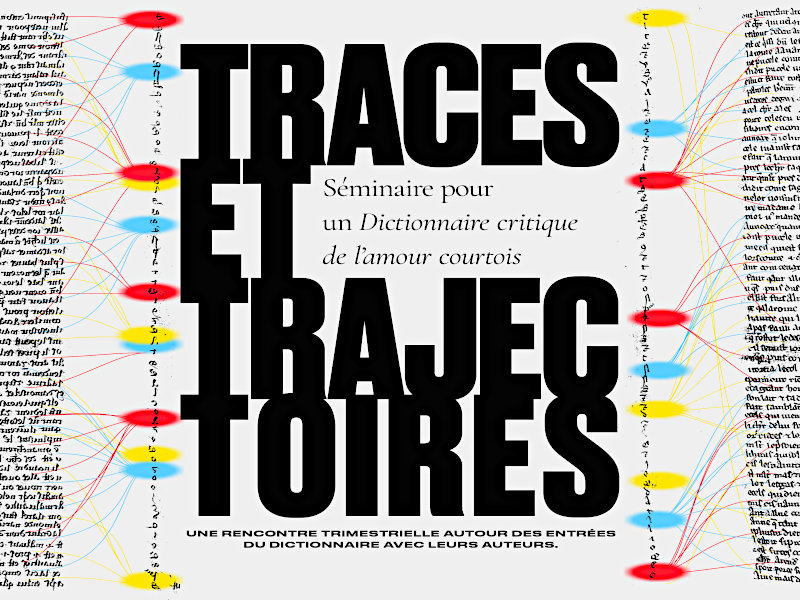

Seminar series “Traces et trajectoires. Pour un dictionnaire critique de l’amour courtois”

Seminar series which will run for three years with quarterly sessions. The events are organised by Jean-René Valette, Hadrien Amiel, and Valeria Russo, in collaboration with the research unit EA4349 “Études et édition de textes médiévaux”, Sorbonne Université Lettres, and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, funded by Initiative Circulations médiévales (Alliance Sorbonne Université) and the European Union (HE MSCA PF – MEDLUNI, GA n° 101149368).

|

|

13 February 2026 - Third session

Salle des Actes, Sorbonne Université, Paris. Speakers: Marion Uhlig – "mort"; Mireille Demaules – "Tristan" |

1 MB |

|

|

12 December 2025 - Second session

Salle G 073, Escalier E, 3rd floor, Sorbonne Université, Paris. Speakers: Sylvie Lefèvre – “cœur”; Alain Corbellari – “discourtois”. |

1 MB |

|

|

23 June 2025 - Inaugural meeting

15:00, Salle des actes, Sorbonne Université, 54 rue Saint-Jacques, Paris. This seminar hosts presentations by contributors to the Dictionnaire critique de l’amour courtois. |

6 MB |

Research outputs

- Valeria Russo, “Watriquet de Couvin: dal trattato alla scuola, dal clerc al maître”, Carte Romanze [ITA], 13:1 (2025), pp. 163-187.

This study offers a new critical edition of the “Dit de l’escole d’amours” by Watriquet de Couvin, exploring its role within the medieval didactic tradition. This text diverges from the “traités d’amour” in verse of the late 13th century, aiming at building a lyric-argumentative text with an edifying purpose. Through intertextual dialogue with Jean de Meun’s “Roman de la Rose”, Watriquet shapes a discourse on love as a vehicle for ethical and moral transmission.

Outreach and public engagement events

- 26 February 2026 3.00-5.00 PM - MEDLUNI at the Scuola Superiore Meridionale, via Mezzocannone 4, Aula 1, Naples, Italy

One of the research strands of MEDLUNI will be presented at the seminar for PhD candidates and students of Testi, Tradizioni e Culture del Libro [ITA]. The seminar is organised by Paolo Di Luca and Laura Minervini. Title of the lecture: «Personalità, scriptoria e biblioteche intorno all’università di Parigi verso il 1250». - 27 September 2025 9.30 AM - MEDLUNI at the Festival del Medioevo, Gubbio (Centro Santo Spirito, Piazzale Frondizi 17)

As part of the 2025 edition of the Festival del Medioevo, Valeria Russo will deliver a lecture on “clerici vagantes” and university migrants.

The Festival del Medioevo [ITA], organised by the Cultural Association Festival del Medioevo in collaboration with the Municipality of Gubbio, is a major public event that each year brings together scholars, journalists, and a wide audience to reflect on the medieval past through lectures, debates, and cultural initiatives. The theme of the 2025 edition is “The Journey”.

Blog

A Lesson in Humility

There was not only a literature ‘by’ scholars and clerics in the Middle Ages, but also a lively literature ‘about’ them. In Italian “novelle” and French “fabliaux”, masters and students often appear in a comic light: poor, drunk, unwell, cunning, or unbearably full of themselves.

But beneath the humour lies much more than mockery. These tales offer us vivid glimpses of medieval academic life: how teaching unfolded in the lecture hall, what was debated in class, how students lived beyond university walls, and what was said of those who preferred the tavern to the library.

Through sources like these, literature becomes a window onto the everyday life of medieval universities, revealing both their dignity and their disorder.

With this in mind, we begin a short series of posts presenting medieval vernacular texts, paired with an English translation, each one opening a small window onto the academic world of the Middle Ages.

Our starting point is the “Novellino”: a substantial collection of short prose tales, often regarded as the most important precursor to Boccaccio’s “Decameron”. The collection was composed, at least in part, in late thirteenth-century Florence by an anonymous author, and it survives in several versions.

Among these tales, number XXXV places a professor of medicine and his student at the centre of the narrative, firmly set within the familiar scene of a university lecture. Beneath its playful tone, the story reveals how students might debate with their masters, carry out experiments, and contribute to the continual revision of scholarly knowledge.

The “novella” suggests pages alive with comment, exchange and improvisation, the written trace of minds thinking together in real time. Yet it is also, quite plainly, the tale of a master who proves to be rather less sharp-witted than his own student.

The central figure of the tale is Master Taddeo: the Averroist physician Taddeo Alderotti (1223-1295), mentioned by Dante in the Commedia (Par. XII, 83). Born in Florence, he spent most of his career in Bologna, where he taught at the Studium from 1260 onwards. He rose quickly to prominence thanks to the success of his treatments. His reputation rested not only on his medical practice, but also on his commentaries on Hippocrates and Galen.

Below is the text of the “novella”:

Maestro Taddeo, leggendo a’ suoi scolari in medicina, trovò che, chi continuo mangiasse nove dì di petronciani, che diverebbe matto; e provavalo secondo fisica.

Un suo scolaro, udendo quel capitolo, propuosesi di volerlo provare. Prese a mangiare de’ petronciani, et in capo de’ nove dì venne dinanzi al maestro e disse:

«Maestro, il cotale capitolo che leggeste non è vero, però ch’io l’hoe provato, e non sono matto» e pure alzasi e mostrolli il culo.

«Iscrivete» disse il maestro «che provato è; e facciasene nuova chiosa».

“Il Novellino”, Guido Favati (ed.), Genova, Bozzi, 1970

English translation:

Master Taddeo, while giving a lecture in medicine to his students, came across a passage stating that anyone who ate aubergines continuously for nine days would go mad. And he supported this claim according to the principles of natural sciences.

One of his students, having heard this argument, decided he ought to put it to the test. He began to eat aubergines, and at the end of the nine days came before the master and said:

“Master, the topic you read is not true, for I have tested it myself and I am not mad.”

Then he stood up and, by way of proof, bared his backside to the assembled class.

“Write it down,” said the master, “for it has now been tested! And let a new commentary be added to the text.”

A Feminist Sidenote in a 19th-Century Study on Virgil

For the Middle Ages, Virgil was more than a poet. In the medieval time, Virgil was a prophet: the one who foretold the coming of Christ. He was a magician: the supposed inventor of the “Bocca della Verità,” still standing in Rome today. He was also a disgraced lover: disappointed and mocked by women.

We speak of him because Virgil and his works were an obsession among the clerici. Yet he was also a source of torment, bound up with the vexata quaestio of whether it was legitimate to read him at all: as a pagan poet, could one truly nourish the mind and soul on his words?

Moreover, numerous tales about Virgil — recounting his life and adventures, and casting him as a hero of narrative — appeared across medieval texts (fabliaux, exempla, romances, historiographical works). One of these stories, repeated from one context to another, served to reinforce the misogynistic spirit that pervaded the world of the literati.

It is precisely on this strain of misogyny that an old scholarly voice stumbles: “Virgilio nel Medioevo” by Domenico Comparetti, published in Italy in 1872 in two volumes. In the first volume, Comparetti examines the interpretation of Virgil’s works within medieval literature. The second volume, for its part, is devoted to what Comparetti defines as the “popular legend” of Virgil. There, he examines the beliefs associated with the poet.

Needless to say, “Virgilio nel Medioevo” shows the kind of philological naïvetés one might expect from a work of 1872.

There are, however, passages in which we can perceive a social and historical awareness which is quite uncommon for the 19th century. It is worth rereading – and applauding – the foresight of the following words. As we read on pages 103-106 of the second volume:

Italian original text

“Coloro i quali sostengono che di molto vada debitrice la donna al cristianesimo e alla cavalleria, evidentemente vogliono farsi illusione in favore di questi agenti storici, contro l’autorità dei fatti. L’ideale della santa e quello della dama degli antichi romanzi, sono prodotti d’idee utopistiche affatto inconciliabili coll’ordine sociale. […]

L’aver santificato il matrimonio, che a molti sembra uno dei grandi meriti della chiesa cristiana, ha l’effetto di una derisione a chi conosce il medio evo ed ha veduto dappresso tutta quella immensa falange di uomini autorevoli, che ad ogni occasione il matrimonio e la donna pongono in discredito colla voce, coll’esempio e collo scritto.

Dall’altro lato e per via opposta, alle stesse mortifere conseguenze spingeva la cavalleria, fiaccando ogni saldezza dei vincoli coniugali, privando la donna della prima base su di cui possa riposare la dignità sua, che è l’onestà ed il rispetto di se stessa.

Così avveniva che, ad onta di certe purissime imagini presentate dall’agiografia e dalla leggenda cristiana, ad onta degli incensi prodigati al sesso femminile nei romanzi, nei tornei e nelle corti d’amore, in verun’altra epoca fosse la donna più turpemente insultata, beffata, svillaneggiata di quello fu nel medio evo, cominciando dai più serii scritti dei teologi e scendendo fino alla poesia ed al teatro da piazza. Una incredibile quantità di racconti e di aneddoti, spesso triviali ed osceni, la cacciavano nel fango e, quel che oggi pare impossibile, non figurano soltanto nei repertori dei giullari che avevano il solo scopo di divertire, ma nei repertori dei predicatori che li narravano dal pergamo col pretesto di cavarne una morale qualsiasi”.

English translation

“Those who maintain that women owe much to Christianity and to chivalry evidently wish to delude themselves in favor of these historical agents, against the authority of the facts. The ideal of the saint and that of the lady in the old romances are products of utopian notions entirely irreconcilable with the social order. […]

The sanctification of marriage, which to many appears as one of the great merits of the Christian Church, is in fact a mockery to anyone who knows the Middle Ages and has seen up close that immense phalanx of authoritative men who, on every occasion, brought marriage and woman into disrepute — by their words, by their example, and by their writings.

On the other hand, and by an opposite route, chivalry led to the same deadly consequences, undermining every firmness of conjugal bonds and depriving woman of the very foundation upon which her dignity might rest — namely, modesty and self-respect.

Thus it happened that, despite the purest images presented by Christian hagiography and legend, and despite the incense lavished upon the female sex in romances, tournaments, and courts of love, in no other age was woman more shamefully insulted, mocked, and vilified than in the Middle Ages — beginning with the most serious writings of the theologians and descending to the poetry and street theatre.

An incredible quantity of tales and anecdotes, often coarse and obscene, dragged her through the mud — and, what seems impossible to us today, they appeared not only in the repertoires of jesters, whose only aim was to entertain, but also in those of the preachers, who recounted them from the pulpit under the pretext of drawing from them some moral lesson”.

Comparetti turns to this episode because one of the best-known medieval tales featuring Virgil as its protagonist displays a particularly uncontrolled strain of misogyny. As he writes, “It is this persecutory spirit that pervades the oldest part of the Virgilian legend concerning women.” Here follows a brief summary of the story.

Virgil falls madly in love with the emperor’s daughter. But the young woman, instead of returning his affection, decides to make a fool of him. Pretending to accept his advances, she tells him to come secretly to her room — she’ll hoist him up in a basket to her tower window at night. Full of joy, Virgil climbs in. The basket rises halfway… and stops. There he hangs, suspended in mid-air until morning. When daylight comes, all of Rome bursts out laughing at the sight of the great scholar dangling helplessly before the crowd. The emperor threatens him with punishment, but Virgil’s humiliation burns deeper than any fear. To avenge himself, he casts a spell: every fire in Rome suddenly goes out, and the only way to relight it is through the body of the emperor’s daughter herself — one by one, each Roman must come to her backside for flame. The emperor’s daughter was placed in the public square and had to endure that long torment, until the Romans regained their fire. And Virgil had his revenge.

In recounting this tale, Comparetti takes an early and remarkably lucid stand — not only against the misogyny of his sources, but also against the overly idealised conceptions of womanhood found in certain critical traditions, many of which, it must be said, remain fashionable even today.

Wandering Clerics and Wandering Books

Tracing patterns of academic migration makes it possible to reconstruct the broader routes through which knowledge circulated across medieval Europe. At the centre of this network stands Bologna, whose university provides the clearest point of departure.

From the twelfth century onwards, Bologna emerged as the pre-eminent European centre for the study of law. Here, teachers developed new methods of interpreting Roman law, grounded in Justinian’s “Corpus iuris civilis”. Students flocked to the city from across Europe, and in time Bolognese masters themselves carried this expertise abroad, spreading their influence far beyond Italy: especially in France, where the school of Orléans soon emerged as a major centre of legal learning.

Guido de Cumis, of Italian origin and a student of Jacobus Balduinus in Bologna, began teaching at Orléans from 1240 onwards. Simon de Paris left Orléans around 1260 to take up political responsibilities, later becoming royal adviser, chancellor of the Kingdom of Sicily, and rector of the University of Naples. Pierre de Belleperche taught until 1296 before his appointment as Chancellor of France and subsequently Bishop of Auxerre. His influence crossed the Alps: Cino da Pistoia, Italian poet and jurist, drew upon Belleperche’s commentaries in his own legal scholarship.

The trajectories of clerics and books allow us to reconstruct a Europe in motion, where knowledge circulated through migration, teaching, and manuscript transmission, and where the academic career of a poet could profoundly shape his literary life. Figures such as Cino da Pistoia embody this dynamic, leaving their mark on the intellectual and cultural landscape of their time. Cino’s cenotaph in the Cathedral of San Zeno at Pistoia – commissioned in 1337 and completed in 1339 – is emblematic in this sense. This Gothic monument depicts not the poet, but the jurist, represented in the act of teaching his students.

Tracing the Origins of Urban Literature through the Medieval University

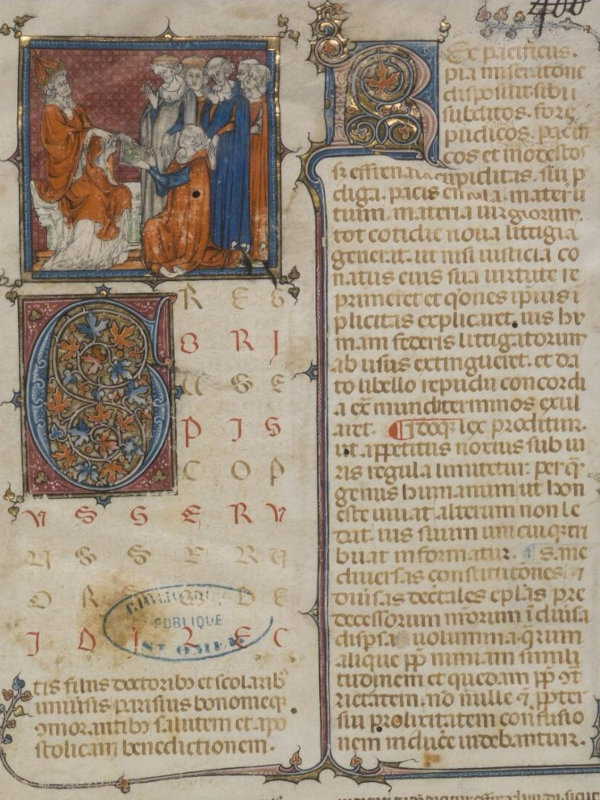

Saint-Omer, Bibliothèque d’Agglomération du Pays de Saint-Omer, 0434, fol. 3r.

© Saint-Omer, Bibliothèque d’Agglomération du Pays de Saint-Omer / Source: ARCA IRHT.

Universities on stage

The parallel emergence of vernacular literature and the medieval university is crucial to our understanding of what may be called urban literature. In many medieval cities, intellectual life and university culture were profoundly interconnected.

Universities projected themselves into civic space through public performances. “Lecturae” and “disputationes” exposed the practices of scholastic learning, offering the wider population a glimpse of forms of knowledge otherwise unfamiliar to most townspeople.

This dynamic left a significant mark on literature. The “débat”, a form rooted in academic pedagogy, resurfaces in the poetry of the “Puy d’Arras”, a medieval community of “trouvères” devoted to poetic competitions. Large audiences gathered to hear poets debate questions such as whether love was ultimately beneficial or harmful.

The theme of the disputatio – a debate between opposing views – plays a key role in the works of Guillaume de Machaut (c.1300-1377) and Eustache Deschamps (1340-1404), both connected to the University of Orléans. In Deschamps, for example, the debate serves to create a reversal within the poem, thus staging a clash of arguments.

But on what other threads does the connection between urban literature and the university depend? One crucial meeting ground lay in the “scriptoria” – shared spaces of cultural production that served both literary and academic communities.

A Parisian network

Within this context, the so-called Master of the Meliacin emerges as a central figure. As documented by Richard and Mary Rouse (vol. I, pp. 104-116), this workshop produced eight surviving codices: three containing “Meliacin” by Girart d’Amiens, and five others featuring works by Adenet le Roi, Gossuin of Metz, and translations by Jean de Meun. The same hand also illustrated Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, MS 3142, dedicated to Marie of Brabant, wife of Philip III of France. This manuscript combines authors well rooted in academic circles – such as Adenet le Roi, Gossuin of Metz, and Jean de Douai – with philosophical and moral compilations, including the “Proverbs of Seneca” and “The Moralities of the Philosophers” by Alart de Cambrai.

Taken together, this evidence reveals the existence of a Parisian circuit of production in the later thirteenth century, where leading literary authors, professional scribes, and illuminators collaborated across both university and literary “milieux”.

The Medieval University as a Hub of Literary Creation?

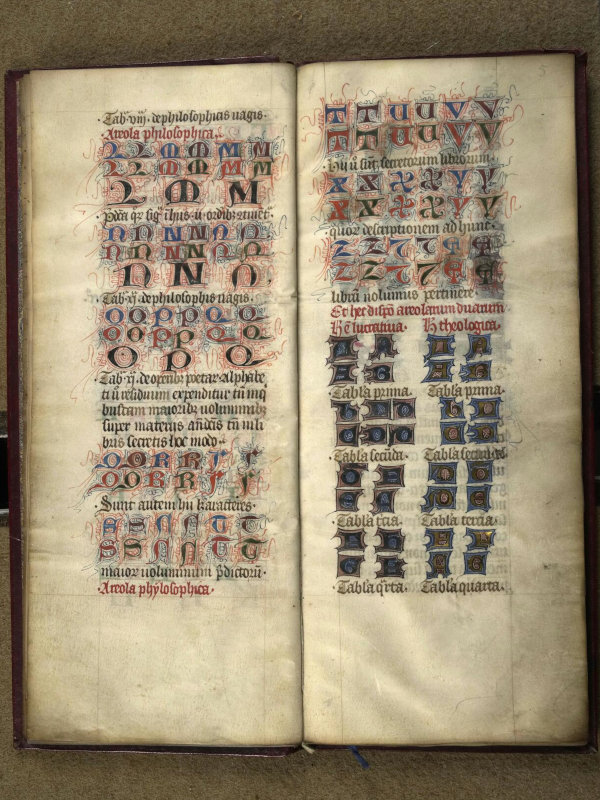

Paris, Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne de Paris, MS 636, fols. 4v-5r.

© Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne de Paris / Source: ARCA IRHT.

The emergence of European universities during the Middle Ages triggered one of the most profound cultural transformations in European history. By reshaping the ways of learning, teaching, and transmitting knowledge, universities contributed not only to the creation of intellectual networks but also to the development of new literary traditions. Yet, the impact of this academic revolution on European Romance literatures has remained largely unexplored. MEDLUNI addresses this scientific gap by investigating how the rise of universities influenced vernacular literary production and by demonstrating the decisive role of academic culture in shaping a common European literary identity.

Between 1220 and 1399, the academic mindset deeply affected the thematic, stylistic, and material features of vernacular texts. Authors who were simultaneously university scholars and literary writers embodied this osmotic process, while manuscripts and texts circulated from one university centre to another, creating unprecedented literary networks. France and Italy, because of their privileged linguistic and cultural ties and their well-documented academic traditions, represent the privileged observatory for analysing these processes.

The project’s ambition is threefold. First, it aims to demonstrate the emergence of a distinctive European literary identity linked to the new academic culture. Second, it seeks to challenge the binary scheme – courtly or ecclesiastic tradition – that has dominated the study of medieval literature, by establishing universities as a third, transnational and transversal pole of literary creation. Finally, MEDLUNI combinins philology, prosopography, codicology, and stylistics to analyse textual mutations, manuscript circulation, and the networks of knowledge created by human mobility.

MEDLUNI will enable future research on other European literary traditions linked to universities. Moreover, the project contributes to broader debates on the cultural history and cultural migrations, thus highlighting the enduring relevance of the Middle Ages for understanding European universities’ heritage.

Team

Valeria Russo

Marie Curie fellow

Ca' Foscari University of Venice, Department of Humanities

Cristiano Lorenzi

Supervisor

Ca' Foscari University of Venice, Department of Humanities

Marion Uhlig [FRA]

Supervisor

University of Fribourg, Department of French

![Marion Uhlig [FRA] Marion Uhlig [FRA]](/fileadmin/user_upload/img/persone-no-unive/Marion-Uhlig.jpg)