COMAL

Cuisine(s) of the Ancient Maya across the Lowlands: Reconstructing Plant Diets through Molecular and Imaging Approaches

Project

COMAL seeks to elaborate on the specifics of plants used in ancient Maya cuisine through a range of technological approaches to determine whether, as a result of social and political transformations, culinary traditions changed through time and across space.

The ancient Maya, known for their sophisticated writing and calendric system, architecture, and arts, lived across a large territory that comprises the modern-day countries of southern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and the northern parts of Honduras and El Salvador.

An aspect that remains understudied are the nuances of their diet, which was rich and diverse given the complex mosaic of ecological zones found across the region, which included tropical forests, mangroves, savannas, but also pine-oak forests in the highlands.

What does the COMAL project add to the knowledge of ancient Maya culture?

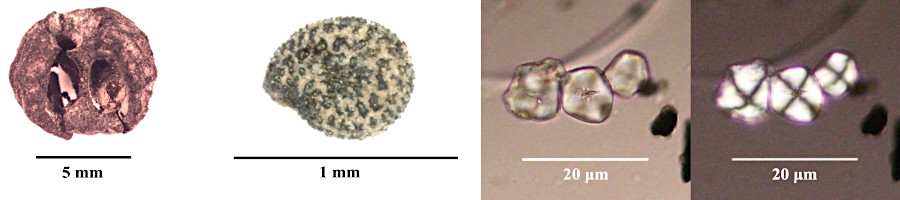

Ancient Maya diets have been studied from a variety of perspectives, including epigraphic sources, artistic representations on ceramics and wall paintings, using rare pre-Hispanic texts, and historical texts from the colonial period written by Spanish chroniclers. While these different resources provide important information, they are imperfect because they are not always objective: glyphs and arts were indeed limited to elites, and colonial texts are narratives written from a European perspective. Archaeobotanical remains are the most direct way to study the plant portion in ancient diets. Macrobotanical remains (visible to the naked eye) and microbotanical ones (requiring the use of powerful microscopes to be visualized), as well as some limited studies on (macro)molecules present in organic residues, have provided to date important information on ancient Maya diets. However, to develop a more comprehensive conceptual view of ancient Maya foodways it is necessary to consider innovative lines of research.

The overarching research question that COMAL seeks to answer is how food practices changed across the Maya region during the Classic and Terminal periods (AD 250-900) in light of numerous political instabilities associated with foreign conquests, wars, and shifting alliances.

Food practices, and their eventual modifications, can be used to interpret how populations adapt to major social and political transformations. It is therefore essential to also consider the ways in which the foods were prepared: using which tools, which combination of ingredients, and the context in which these foods were served.

COMAL seeks to develop a comprehensive methodology to address this still unanswered question by going beyond simply considering the ingredients used, as shared food ingredients does not necessarily imply common culinary and social practices, or common underlying identities.

The project will provide new ways to study ancient diets; more specifically, it will shed new light on ancient Maya culinary traditions, that can be of particular importance to modern-day communities as many are descendants of the ancient Maya. One aspect of the project involves studying how traditional foods such as tamales – maize dough combined with vegetables/meat and wrapped in maize husks or other leaves – were prepared and how they may have changed through time.

Research

The project uses technological approaches that combines microscopic and nanoscopic imaging with spectroscopic and spectrometric techniques to study two main types of archaeological remains: amorphous carbonized objects (ACO) and (bio)molecules. ACO’s will be investigated with different microscopies. To visualize the external structure of the fragments, both a stereoscope (which can magnify up to 50x) and a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), which can magnify thousands of times the object in question, will be used. To visualize their internal structure and determine their composition, a non-invasive and non-damaging imaging technique will be employed: phase-contrast microtomography (micro-CT) provided by synchrotron radiation.

The second type of archaeological dataset will be recovered from the active surfaces of tools used in the transformation and cooking of foods (i.e., grinding stones and ceramics). To characterize the (bio)molecules, a range of spectroscopic and spectrometric techniques will be applied. A select number of modern plants that would have been available in the Maya region during the time period under investigation will first be tested, resulting in a database. The results obtained from the study of archaeological residues will then be compared to this database. Moreover, a select number of plants will also be processed and modified (i.e., cooked, fermented) under controlled laboratory conditions to increase the available datasets.

COMAL with contribute significantly to our understanding of ancient Maya culinary practices and how they may have been transformed through time and across space.

Team

Clarissa Cagnato

Marie-Curie Fellow

Antonio Marcomini

Supervisor

Elena Badetti

Researcher

Alessandro Bonetto

Technologist

Secondment

A period of secondment at the SYRMEP beamline at the Elettra Synchrotron in Trieste will allow access to micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), which will be used to study the internal structure of the ACOs in a non-destructive manner.