ACTION

Assessing Climate TransItion OptioNs: policy vs impacts

Outreach

COP27: among negotiations and side events

27/11/2022

Toward the end of the year, and in particular at the end of November/beginning of December, there is the COP, whose acronym stands for Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC. It’s the name of the annual Conference on Climate Change within the United Nations. It is the place where formal climate negotiations happen as well as the opportunity for researchers across the world to present their research in front to a policy-oriented audience.

This year, following the usual rotation among the UN groups, the COP 27 has been hosted by Egypt for the first UNFCCC Conference in a developing country after COP22 in Marrakech in 2016.

A strong emphasis has been placed on the fact that this was an “African COP”, whit a focus on the priorities of developing countries, such as adaptation, climate finance, and loss and damage (L&D). The issue of loss and damage (L&D) has managed to enter the formal agenda of the Conference for the first time and, although a very thorny debate, the need to establish "funding arrangements" including a fund within the UNFCCC for the most vulnerable countries was agreed. This represents a huge success for less developed countries on an issue that has been part of the negotiations for about twenty years but that never managed to get economic recognition. Key elements are still open, such as how to make the new fund operational, where the funds will come from and how to distribute them, but the newly appointed Transitional Committee has one year to provide recommendations, to be presented at COP28 in Dubai in 2023.

In terms of personal engagement, I was glad to participate in two events organized at COP27.

The first, What is Italyʼs pathway to limit global warming to 1.5°C?, was organized by Climate Analytics and ECCO, on November 14 in the Italian Pavilion. The debate started from the presentation of the 1.5°C scenario options for Italy followed by a round table discussion. Many interesting points were touched, including the latest findings of the IPCC assessment reports to then move toward the challenges posed by the Italian context, mentioning also some of the tools and policies we might build upon. More specifically, I focused on the need for an accelerated action to avoid disruptive impacts of climate change in light of the residual window of opportunity to keep 1.5 within reach.

In addition, on November 17, I was involved in another event, an official side event jointly organized by the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change (CMCC), the European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists (EAERE) and Società Italiana per le Scienze del Clima (SISC) on "Launching a European Climate Science Assessment Mechanism for Policy Support". In this case, the perspective embraced the European context, touching different aspects of the European Union’s climate change policy and providing an assessment of key tools and potential improvements. The event involved international speakers from both the academic and policy-making environment. I had the chance to present some of the results of my MSCA project focusing on the role of energy prices in the relation between temperature extremes and mortality and an evaluation of potential interaction between future mitigation policy, adaptation, and potential trade-offs for consumers. A recording of the event is available on Youtube. Presentations had the objective to show the role of scientific research in helping design European policies.

These events represented some of the key communication outcomes planned under the ACTION project to improve the impact of research findings beyond academia to reach also policy makers and civil society.

Marie Sklodowska Curie Ambassador at NAFSA 2022 in Denver

10/06/22

In the past days, I participated in the NAFSA 2022 Annual Conference & Expo, held in Denver (Colorado) from May 31 to June 3, 2022, as a member of the European Commission’s team. The conference is a huge event, organized by Association of International Educators, the world’s largest association dedicated to international education and exchange, to share and discover the latest innovations, programs, and best practices in the field of international education exchange and students support to go abroad. The global international education community met at NASFA in person (after two years) and online, showcasing their activities, program offers and building new exchange networks.

NAFSA 2022 theme was “Building Our Sustainable Future”, aimed at focusing on design strategies for our sustainable future success at this critical time of reemergence.

My role at the conference, at the booth of the European Commission, was to provide information about the different EC-funded programs supporting students and researchers’ mobility. These included the Erasmus+, the Joint master’s degree and, of course, the Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellowships. As a Marie Skłodowska-Curie ambassador, I had the chance to present my experience and research and to interact with education institution officers interested in building a connection with European research centers and university.

It was an enriching and very interesting experience that allowed me to meet other fellows participating in various European programs and also to exchange views with some of the EC officers that design and manage the exchange programs we participate in. It was also very exciting to finally travel again and interact with people personally after the Covid-19 limitations of the past two years.

The US' Energy Transition Between Rising Prices and Political Uncertainty

05/01/2022

(this article originally appeared on ISPI)

Worldwide, energy prices recently skyrocketed to their absolute highest level in decades, spreading concerns about their ripple effect for consumers, the economic recovery, and energy security.

The reopening of economic activities, along with colder than expected winter forecasts, have contributed to increasing demand for natural gas, crude oil, and coal from the lows of 2020. Meanwhile, however, supply has not returned to pre-covid-19 production levels yet. The consequent increase of wholesale prices is being passed through to businesses and consumers. In the US, major concerns particularly regard the retail price of heating fuels — such as propane, heating oil, and natural gas — that reached their highest point in several years in mid-October.

The energy prices in the US

According to the US Energy Information Administration estimates, households that primarily use natural gas for space heating (which are the majority, accounting for 48% of the overall population) will spend on average 30% more than last year to heat their homes. However, as pointed out by some experts, prices are actually higher on a year-to-year basis, though this reflects the fact that they were extraordinarily low during 2020 because of the covid-19 economic slowdown. If anything, if adjusted for inflation, they are below the average price of the last two decades. Moreover, U.S. natural gas price is much lower than its European counterpart, where price hikes have been accompanied by the fear of power outages due to low supply from Russia.

This notwithstanding, the impact on consumer categories that already bear a high energy burden may be significant. A recent report shows that in 2017, well before the Covid-19 recession, 13% of US households (15.9 million) faced a severe energy burden as they spent over 10% of their income on energy bills, against a national average of 3%. They are part of a broader number of people who are also considered to be struggling with high energy expenditure and that represent 25% (30.6 million) of US households. Among them, a disproportionate number of Native American, Black, and Hispanic households as well as older adults and families residing in low-income multifamily housing face a higher-than-average energy burden.

The economic downturn imposed by the pandemic restrictions and current inflation rates — which have reached a 30-year high — further worsen energy insecurity and lead to higher energy burdens. Against this backdrop, affected families may face a “heat or eat” dilemma, as they struggle with allocating resources and may be faced with the choice of picking between heating their homes and feeding themselves and their children. Emerging research focusing on the US finds that higher heating prices could also affect public health as a byproduct of lower heat use and other health-promoting spending; thereby increasing winter mortality among the most vulnerable households.

From an environmental point of view, one might expect that higher oil and gas prices may encourage — and speed up — renewables’ development. However, without a stringent carbon price, the climate benefits of a reduced use of these fuels are rather limited and can be partially cancelled out with cheaper coal. That is the current scenario, as increased and more volatile natural gas prices have resulted in the US electric power sector generating more electricity from coal-fired power plants, reversing a decreasing trend that had started in 2014 on top of threatening the Biden administration’s emission reduction. Though 2020 was a record year for renewable energy and additions to wind and solar capacity were planned in 2021, coal and natural gas remain the largest sources of electricity generation in the country. Non-hydro renewables accounts for 12.5 percent of total electricity generation.

Biden’s Policies to control prices and foster the energy transition

President Biden has been under pressure to solve the energy price crisis while, at the same time, he has also been trying to pass important pieces of legislation to boost investments and clean energy technology.

Late in November 2021, he announced the release of 50 million barrels from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve as an effort to increase oil supply and push down global prices. Other major oil importers, including China, India, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom have agreed to do the same. The decision came after previous calls to push OPEC+ countries to speed up their production (and give away their profit margins) fell on deaf ears. Crude oil price actually decreased in November and December, though it is still over 30% higher than at the start of 2021. However, fears that the Omicron variant could trigger new lockdowns — compounded by a relatively mild beginning of the winter months — seem to be the real drivers of lower energy prices, rather than the impact of U.S. inflows into the market, which are considered too small to significantly alter supply-demand dynamics. Above all, the White House’ and other governments’ decision risks to further exacerbate relations with OPEC+ countries, which have so far decided to stick to their original plan of gradually increasing monthly supplies. Beyond the fight against energy prices, other ongoing issues, including the Iran nuclear deal talks and the already difficult relationship with Saudi Arabia suggest that energy policy will remain at the top of the US geopolitical agenda in the near future.

Domestically, President Biden faces many challenges, as he has been criticized for prioritizing emission reduction targets and therefore limiting domestic oil and natural gas production. The Biden administration is indeed pushing for substantial investments in the clean energy transition. After a tough discussion, Congress recently passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, a bipartisan deal that allocates $500 billion funds for new infrastructure over the next five years, including clean energy infrastructure and climate resilience. The law is the first part of a two-pronged plan, the Build Back Better Act (BBB), whose second part got the House’s approval and is now awaiting to be considered by the Senate. Overall, the Act would provide $2.1 trillion in new spending in the form of grants, loans, credit support, and direct funding to reinforce existing programs as well as launch new ones. Of these, $555 billion will be aimed at redirecting investments toward renewable deployment, clean hydrogen, development of carbon capture and other low-carbon energy technologies, but also improvements of the electrical transmission grid and the construction of charging stations to accelerate the transition to electric vehicles. The Act also establishes programs to support energy efficiency, wildfire mitigation, domestic manufacturing of batteries, solar panels, wind turbines, and research and development. Beyond clean energy tax credits, which represent about 60 percent of the energy expenditure ($320 billion), and clean energy investments ($110 billion), an important piece of the legislation are the resiliency investments ($105 billion) that aims at climate proofing infrastructure to make them more resilient and avoid the kind of disruptions that we have witnessed in previous extreme cold weather events. Furthermore, important measures are planned to ensure a more equitable distribution of the economic opportunities that come with clean energy investments, such as grants and loans for local cooperatives to increase renewables use and energy efficiency and balance the costs of coal replacement.

If passed, the BBB would be the single-largest investment in clean energy innovation and infrastructure in US history, and it is expected to put the country on a pathway consistent with its commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels by 2030. However, the unfeasibility to approve any type of carbon price initiative at the federal level makes the approval of the BBB an opportunity the US can’t miss out on if it wishes to catch up on the global climate agenda and develop an energy infrastructure that is less vulnerable to price changes. Along with other crucial reforms around transport, digitalization, and education, the plan also offers a great potential for the economy and job creation — estimated to amount to 3 million per year. Much will depend on the private sector’s response as well as on bipartisan support to finalize — and implement — it.

COP26: There Is No Mitigation Without Cooperation

30/11/2021

(this article originally appeared on Foresight)

The rules on the cooperative approaches, referred to in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, were one of the key agenda items to be agreed at COP26. Article 6 provisions represented, indeed, the last missing piece of the Paris rulebook, whose major components were approved at COP24 in Katowice (Poland).

In Glasgow, countries finally found an agreement on a thorny issue, whose rules have the potential to support the achievement of the Paris Agreement’s goals at a lower cost and provide larger incentives for private sector investments.

A technical and political issue

Cooperative approaches include voluntary mechanisms that, within the Paris Agreement, will allow countries to collaborate in pursuing higher ambition.

According to Article 6, cooperative approaches can take three forms:

- voluntary cooperation, including the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) as per Article 6.2

- a new mechanism to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and support sustainable development, as per Article 6.4

- non-market mechanisms, as per Article 6.8

In other words, these three paragraphs open to the door for countries to bilaterally trade emission reductions, or other types of mitigation outcomes, to develop a new carbon crediting mechanism, often referred to as the “Sustainable Development Mechanism”, under the supervision of a UN body, for the trade of emissions reductions, and to cooperate in other forms that don’t involve trade.

Major points of discussion in Glasgow were related to how to preserve environmental integrity and avoid double-counting of transferred emission reductions, how to ensure that these mechanisms deliver increased ambition and progression, how much of the share of proceeds has to be dedicated to adaptation in developing countries, how to integrate a language on human rights protection and rights of local and indigenous people.

Effective rules on transparency, ambition and robust accounting would allow these mechanisms to unlock further mitigation potential and leverage private investments. On the contrary, poorly designed rules would offer loopholes, which could undermine the Paris Agreement’s fundamentals. Tough negotiations on technicalities went hand in hand with complex political discussion, with some countries more reluctant than others to the idea of limiting the way they can achieve emissions reductions.

What the negotiating texts say

In particular, the approved documents clarify the definition of “Internationally transferred mitigation outcomes” as real, verified and additional emission reductions and removals, including mitigation co-benefits resulting from adaptation actions or economic diversification plans. These emission reductions have to be generated after 2020 and measured according to IPCC methodologies and metrics, or metrics agreed among Parties in the case of non-GHG targets.

Each party to the Paris Agreement engaging in the transfer of mitigation outcomes shall apply corresponding adjustments, meaning that the same emission reduction cannot be claimed by more than one country as counting toward the achievement of their climate commitments, or by more than one entity in the case the country allows others to claim it for other purposes. The decision text offers different methodologies to follow according to the type of targets, along with rules on periodical reporting and review to ensure transparency, accuracy, and comparability of information.

A database and a centralized accounting and reporting platform will be created and managed by the UNFCCC secretariat to keep track and review information provided by countries.

The new sustainable development mechanism will rise from the ashes of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), created under the Kyoto Protocol. The decisions on article 6.4, indeed, appoint a new Supervisory body that will review the features of the CDMs in order to apply the revised rules by the end of 2023. Moreover, CDM projects and activities will be allowed to transition into the new mechanism through 2025, as will the certified emission reduction units from CDM projects emitted from 2013 onwards. However, they can only be used towards the first NDC achievement and will be classified as pre-2021 emission reductions.

The name of the emission reduction units achieved under the new mechanism is A6.4ERs and they may be used towards NDCs achievement or for international mitigation purposes. Both public and private entities can participate in emission reductions activities, which should achieve emission reductions that would not take place otherwise. To ensure that the new mechanism contributes to the so-called “overall mitigation in global emissions” (OMGE), a minimum of 2% of the A6.4ERs will be cancelled out at their issuance.

In addition, another 5% of each of A6.4ER will be transferred to the Adaptation Fund to support particularly vulnerable developing countries in coping with the cost of adaptation.

In this case, as well, corresponding adjustments need to be applied when emission reductions are transferred, with the exception of the CDMs credits.

As for the non-market mechanisms, the guidelines identify some initial focus areas, such as adaptation, resilience and sustainability; mitigation measures that also contribute to sustainable development; and development of clean energy sources. Overall, there is a call to both the public and private sectors as well as to research and civil society to contribute by proposing, developing, and implementing non-market cooperative mechanisms, with an invite to parties and observers to submit examples and experiences. A Glasgow Committee on Non-Market Approaches is established, and it will meet twice a year up to 2027, to further advance the development of Article 6.8’s cooperative mechanisms.

In implementing actions under the three mechanisms, countries have to respect and promote human rights, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities and of other people in vulnerable situations as well as ensure gender equality and intergenerational equity.

Beyond words

The guidelines on Article 6 mechanisms have been welcomed with mixed feelings, as some observers and stakeholders point to the positives whereas others focus on the potential weaknesses offered by the text.

The agreement reached in Glasgow is undoubtedly not perfect, but it offers a package of detailed rules to govern cooperation among countries in a transparent and accountable manner. Rules on partial cancellation and corresponding adjustments ensure that key elements to preserving climate integrity are now on paper, although with some weak spots.

The corresponding adjustments, in particular, represent a crucial component to avoid double counting of emission reductions towards both the achievement of NDCs and also for other mitigation purposes. Whereas for the former it is pretty clear that no more than one country can use the same emission reduction unit in its national account, some methodologies in article 6.2 and the language on the use of emission credits for other mitigation purposes in article 6.4 offer potential for double-counting of emissions used in the aviation sector carbon offsetting scheme (known as CORSIA) or in other voluntary carbon markets.

The carry-over of the Kyoto era’s projects and emission reductions also raised widespread concern. From a methodological and procedural point of view, reviewing and improving existing rules will save nearly two decades of work on validations, exchanges, and registries. However, in terms of climate ambition, they actually represent emission reductions that already took place and therefore are not additional. An analysis by the NewClimateInstitute widely circulated during negotiations estimates that up to 2.8 billion carbon credits could flow into the Paris Agreement from these projects. The possibility of using them only for the first NDC and the fact that such emissions reductions will be clearly labelled (and therefore easily identifiable) may somehow limit their usage.

Overall, how much governments and private companies will choose to exploit these potential loopholes, also considering the increasing request of carbon offsets, will be of crucial importance for the success of these mechanisms.

2030: how we made it / 2030: come ce l'abbiamo fatta

30/10/2021

I had the pleasure to participate in the 6th podcast of the 2030: How We Made It series [ITA], organized by the Sustainable Ca' Foscari Office and the Office for Communication and Promotion of the Ca' Foscari University of Venice. The series takes place in 2030, in a nicer, fairer and more sustainable future, where all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been achieved, and imagines retracing the efforts that the Ca’ Foscari community put in place in the previous ten years to help reaching them.

The topic of the podcast is the climate change, which is directly linked to the Goal 13 “Climate Action”, the Goal 10 “Reduced Inequality” and the Goal 15 “Life on Land” and to many others goals indirectly. It is an interesting discussion of the different aspects of climate changes, the strategies to limit temperature increase and how better adapt to the impacts.

The podcast is in Italian and is accessible on the website of Radio Ca’ Foscari [ITA] and on Spreaker [ITA], or you can listen it below.

A special Earth Day summit

27/04/2021

In the wake of his renewed climate commitments, U.S. President Biden invited 40 World leaders to participate in a virtual Climate Summit starting on the Earth Day, April 22, 2021.

During the two-day gathering, United States and other countries announced new climate objectives with the aim of accelerating the emission reductions needed to keep the increase in global temperature below 1.5°C, as established by the Paris Agreement.

The first day started with a session dedicated to rising climate ambitions, with announcements from many major emitters.

Some examples include:

- Japan pledged to cut emissions 46-50% below 2013 levels by 2030 (current goal 26%).

- Canada aims at strengthening its current NDC (30% below 2005 levels) to a 40-45% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030.

- The European Union confirmed its commitment to make into law the Climate Pact’s target of reducing net emissions by at least 55% by 2030 and a net zero target by 2050.

- China planned to join the Kigali Amendment, strengthen the control of non-CO2 greenhouse gases and phase down coal consumption.

- In a departure from previous climate change approach, Brazil committed to achieve net zero by 2050, end illegal deforestation by 2030, and double funding for deforestation enforcement.

- India announced the launch of the “U.S.-India 2030 Climate and Clean Energy Agenda 2030 Partnership” to mobilize finance and speed-up clean energy innovation.

- The United Kingdom committed to pass a law with the objective of reduce emissions by 78% below 1990 levels by 2035.

- The Republic of Korea pledged to end public overseas finance to coal and strengthen its NDC to be consistent with its 2050 net zero goal.

- South Africa announced that it intends to strengthen its NDC and shift its intended emissions peak year ten years earlier to 2025.

The summit, which saw the participation of Vice President Kamal Harris and the members of the President’s Cabinet, Special Envoy for Climate John Kerry, and National Climate Advisor Gina McCarthy, also touched upon several other key topics, including adaptation and resilience, innovation and technology, economic opportunities and green jobs.

It was an important event to put countries on the road to the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 26), which will be held in November in Glasgow, after that last year conference was cancelled. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres commented: “the tide is turning for climate action”, although urgent immediate action is needed to turn words into practice.

Summary and video recordings of the events are available on the official website.

Energy poverty: drivers and opportunities in the EU

22/04/2021

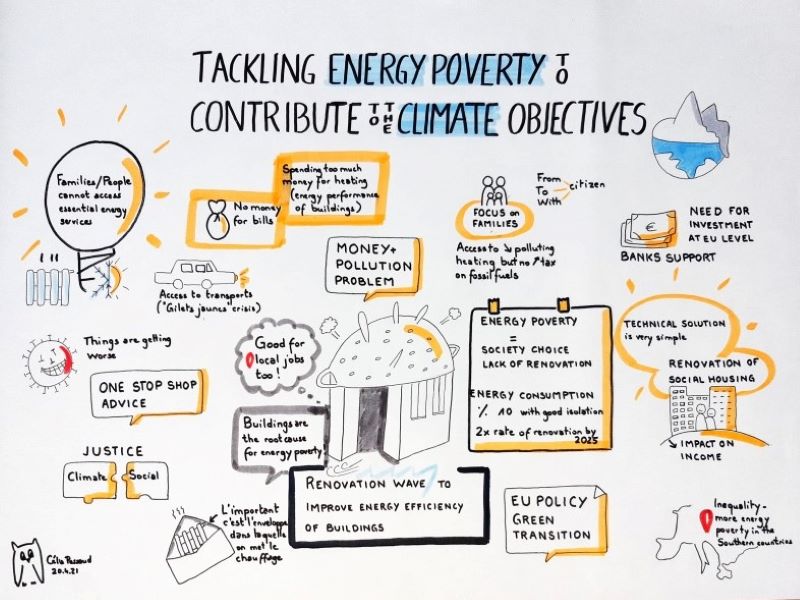

On April 20th, I attended the conference on "Energy poverty at the crossroads of the European Pillar of Social Rights and the European Green Deal", organized by the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC).

The topic is relevant for my MSCA research as the first strand of research we are approaching investigates the potential impact of energy prices in the relation between temperature extremes and mortality risk. The detrimental effects of extreme temperatures on excess mortality are well recognized in the literature. Both mitigation policies and adaptation strategies are crucial to protect households, especially the most vulnerable ones such as seniors and people with cardio-vascular diseases. However, tradeoffs may emerge as ambitious emission reduction policies are expected to lead to energy price increase, actually reducing the ability of households to protect themselves through a larger use of heating in winter or air conditioning in summer.

The event addressed many important issues related to the topic. In particular, the drivers of energy poverty, including low income, poor housing conditions and energy prices but also the opportunities, offered by both the European Green Deal and the post-Covid 19 recovery packages, to put in place measures to identify vulnerable households and support them in dealing with both temperature stress and energy bills.

The video recordings of the event are available online.

One trip around the Sun, one year of ACTION

5/02/2021

One year ago my MSCA experience started. Despite all the hitches and difficulties of starting a project during a pandemic the activities are going on. There have been some changes, agreed with my supervisors, compared to the original schedule. In particular, we decided to start with the last research deliverable, for which the research need seems more pressing.

This strand of research focuses on the analysis of the role of residential energy prices in the temperature-mortality relationship. We decided to start from the European cities in a time span that ranges between 1990 and nowadays.

Starting point is the well-established literature on the impact of extreme temperatures on health and other wellbeing indicators as well as the recently emerging studies on the impact of climate change policy on mortality through energy prices.

However, data mining resulted more challenging than expected. The huge availability of systematically collected data at county level for the United States still seems a dream for the European context. Mortality and population data are collected by Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, which collects information form the national statistical offices of Member States. There are different databases to explore in order to get city-level information: the urban audit database, the database on metropolitan regions and the NUTS3 data. A compromise has been however necessary between granularity, time coverage and quality of the data. Data about temperature and energy prices are more easily accessible through consolidated sources.

Initial research efforts were mostly dedicated to select data that maximize the number of observations in order to have more reliable results. We estimated the impact of temperatures and energy prices on mortality rate using a panel regression model with year and city fixed effect.

Preliminary results are interesting and will be presented later in the spring term during one of the weekly Energy Policy seminar organized by the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. The plan from now to that time is to use the estimates on historical data to simulate the joint impact of temperatures and energy prices on mortality rates in the next decades.

It is also time to start thinking to the next deliverable that will be focused more on the analysis of policy issues.

What does Biden’s victory mean for climate policy?

07/12/2020

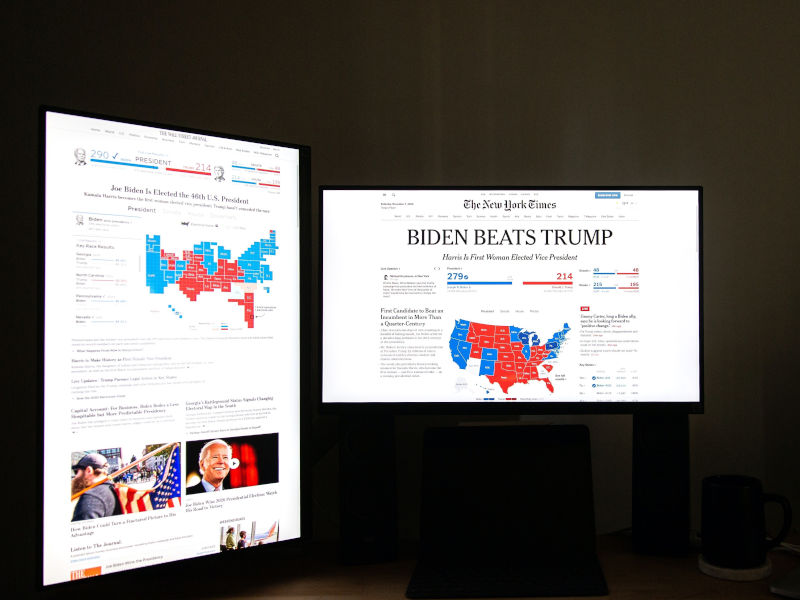

As a result of November 3rd elections, Joseph R. Biden Jr. was elected the 46th president of the United States. We maybe will remember the 2020 U.S. presidential race as the most controversial of the last decades, following one of the most divisive and expensive political campaign.

From a climate change perspective, Biden’s victory means a renewed hope about the return of the US administration on the international climate scene. After four years characterized by President Trump’s skepticism of climate change and his federal action mainly aimed at dismantling Obama-era climate change and environmental policy measures, the challenge for the new President-elect is not only to rebuild domestic climate policy but also to rebuild the international credibility of the United States in the climate policy arena.

The most awaited action, and one of the first promised by the new President-elect, is to re-enter the Paris Agreement on his first day in office. Beyond the formal process, the main expectation is that the United States will be back with an ambitious and courageous move toward the decarbonization of their economy. Already at the time of President Obama, further action would have been required to achieve the objective, proposed under the UNFCCC, of reducing GHG emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025. In addition, some of the major emitting countries have, meanwhile, increased their long-term mitigation targets, as in the case of the European Union that, with the Green Deal, among the others, foresees a climate neutrality target by 2050 or China that in September announced the adoption of a carbon neutrality goal by 2060.

During the electoral campaign, Biden unveiled the most ambitious climate plan ever proposed by any other nominee. He stated that climate change is one of his four priorities (along with Covid-19, economic recovery and racial equity) and that he will work to put the United States on a zero-carbon path by 2050. He pledged a $2 trillion investment plan to decarbonize the economy and create jobs.

However, given the strict election victory, it is unlikely that he will be able to pass an economy-wide federal plan, such as a carbon price mechanism. There may be common points with Republicans on innovation, renewables and technology that he could decide to pursue to have a bipartisan consensus, even though also among the Democrats there are some reticent on climate action.

It is likely he will have to proceed, as President Obama did previously, through executive orders to be implemented via the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or the energy and transport departments. Overall, therefore, the question is what the Biden/Harris administration will be able to do, considering the U.S. political context and electoral result. For sure they have to use every lever throughout the federal government and, learning from Covid-19 experience, start again to rely on science and international cooperation.

Talking about challenges and future prospects in climate change global policy

19/11/2020

On November 14th, I took part to the “Regenerative Sustainability”, a day of debate around different aspects of sustainability [ITA], usually held in Ravenna (Italy) but, as many other events, this year it was taking place completely online. In particular, I was invited to speak in the session on climate change global policies, during which I had an interesting debate with the colleague Elena Drei.

I was glad to accept this invitation, which was an opportunity to talk to a broader public than the academic audience.

The debate touched several points related to current climate policy landscape, the options to prioritize and of course the perspectives for future action in the light of the recent results of the US elections.

The event was in Italian, and the recording is available on YouTube. For non-Italian speaking persons, I summarize the main points below.

The first issue concerned the policy interventions that, according to me, the international community needs to urgently prioritize from a climate policy perspective. Although, the policy debate involves multiple important aspects, the first three policy measures that would be beneficial for the climate policy action are:

- Put a price on carbon emissions. From an economic point of view, to put a price on carbon is the most-efficient, least-costly way to reduce emissions. It means to apply the “polluter pays” principle. More and more countries and local administrative units are currently implementing policies to reduce emissions. However, the price of emissions in the initiatives currently in place is too low. According to the IPCC, a scenario consistent with an increase of the global temperature below 2°C requires an emissions price of at least 50 euros per ton already in 2020, to increase afterwards.

- Eliminate subsidies to fossil fuels. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that consumer subsidies accounts for more than 300 billion dollars a year. This creates a distortion in the energy market, which, through an artificially low price, encourages excessive production and consumption. Subsidies removal, together with a carbon price, would give fossil fuels the right price, redirecting capital flows and investments.

- Prevent that measures to fight climate change negatively impact vulnerable groups. Mitigation measures, including both carbon pricing and subsidies removal, may lead to an increase in the price of energy, thus potentially affecting the energy expenditure of lower income households. Therefore, mitigation policies must be conceived as part of broader policy packages, which take into account possible negative effects in the short term. An important aspect is to explicitly account for fairness, also to support the public acceptance of such policies.

Another key aspect is the interaction between climate change policy and the Covid-19 health emergency, which pushed many other important issues into the background, including the issue of climate change. There is the risk that some climate objectives, which require an immediate action, will become unattainable in a few years. It is true that decreased economic activities are going to reduce this year’s emissions, but much greater efforts are required to stay below 1.5°C and we can only achieve it through targeted investments and policies.

Overall, the climate emergency has a lot in common with the COVID-19 emergency: they are both global problems that involve negative externalities, whose resolution (and delayed action) comes at very high costs. Also, in both cases the consequences affect many and strongly interconnected sectors of our society, such as health, economy, public policy. For this reason, it is necessary to take the opportunity to act in a long-term perspective, and exploit the synergies between economic recovery policies that will be put in place after Covid-19 pandemic and the climate mitigation and adaptation objectives, in order to really set the foundations of a truly resilient society. Research done in the sector indicates that careful economic recovery investments can have positive climate impacts. A positive impact on both the economy and climate change may be expected from interventions aimed at improving connectivity infrastructure, R&D spending, education, clean energy infrastructure and R&D. On the contrary, measures aimed at providing liquidity or tax reliefs bring limited benefits on both long-term economic recovery and climate change.

Finally, the recent victory of Joe Biden in the US Presidential elections opens the way to a new climate-friendly path for the United States. In particular, one of the first actions promised by the new President-elect will be to immediately re-enter the Paris Agreement. However, the main problem for the United States is not only the formal withdrawal from the Paris Agreement but the four years of inaction (or even counteraction) of the Trump administration. Biden’s climate change program is very ambitious, and he is going to face important challenges…but I will address them in the next post.

Be a Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellow at the time of Covid-19

27/07/2020

When I received my Marie Sklodowska-Curie award notification letter, in 2019, I could only think of the three exciting years ahead. With a mix of fear and excitement I started preparing to move in another country, where I would have had the opportunity to work with wonderful people, develop my own project and acquire additional expertise. I was somehow aware of the fact that I was going to face some challenges but the idea that something totally unpredictable, like a pandemic, could change my plans was absolutely far from my thoughts.

Not even at the beginning of February, when my fellowship started amid the first news about rising COVID-19 cases in Europe and the US, I was actually aware of the extent of the consequences.

After the first meeting with my supervisor, I started to participate to the lively Harvard campus activities, including lunch seminars and classes. I started to regularly go to my office, and to have first small chats with my new colleagues…until March 10th , the day Harvard University announced the decision to move all activities remotely to protect the health of its community. I have spent a total of one month at my desk at the Kennedy School.

Project-wise, I would not say that it was so disruptive, as large part of my research can be done anywhere there is a laptop and a good internet connection. Overall, I feel I have been luckier than many colleagues working in the labs or in the field. However, I must admit that being confined home at the beginning of a new project, when exchanging ideas with colleagues or getting advice from experts met at gatherings have an important role, was a bit difficult to manage. Also, the fact that I had just moved in a new country, the worries about health insurance coverage or about the safety of family and friends in Italy, added an unusual mental burden.

Harvard University made a great effort to create an inclusive and effective virtual environment. I was able to keep attending classes remotely and, although many seminar series were cancelled, my supervisor organized different groups of discussion to keep PhDs and postdoc fellows connected. Spontaneous virtual happy hours and social gatherings started to pop up, both inside and outside the working environment. All these activities make me feel part of a huge community, committed to help and support each other. I am grateful also to the European Commission, that promptly showed flexibility in managing the project, even allowing fellows to go back to their home country during this period of remote working. Through the official Marie Curie Alumni Association, I also found that a big Bostonian family of Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellows is there, ready to help, share their experience and make fun to forget the pandemic for a few hours.

Beyond personal feelings, these trying times offer un unprecedented opportunity to reflect on our relationship with the surrounding environment and the type of society we want in the future. This crisis shows us that in a now fully interconnected socio-economic system it is difficult to cope with a public health emergency without causing impacts on other sectors of the economy.

This has a lot in common with climate change. The impacts of climate change involve a wide range of sectors, including health and economics. Climate changes have been indeed defined as a threat multiplier because they interact with the vulnerabilities already existing in our society. For this reason, we need to seize the opportunity to act thinking to the long-term, to exploit the synergies between policies for the economic recovery and climate ones to build a truly resilient society, able to protect the most vulnerable in this and other future challenges.

The peculiarity of policies to combat climate change, however, is that the action of individual governments is not enough. A drastic reduction in CO2 emissions necessarily requires a coordinated response from world countries. The good news is that if we act now there will be less need for policies as aggressive and invasive as the ones we have seen in recent months.

The Paris agreement: key points and future prospects

22/06/2020

December 12, 2015 has taken its place in the history of the fight against climate change as the date on which 195 countries succeeded in finding a common agreement for reducing anthropogenic emissions and handling the impacts of rising global temperature.

After years of negotiations, and with the still fresh memory of the Copenhagen Conference, which in 2009 had failed to produce the desired result, countries met in Paris from November 30th to December 12th, for two weeks of intensive negotiations aimed at defining “a new protocol or other legal instrument with legal force under the Framework Convention, applicable to all Parties.” In carrying out this mandate, entrusted to them in Durban (South Africa) in 2011, national delegates from around the world had to find a compromise on several key issues. The final agreement can be considered a step ahead, albeit insufficient, for reasons we shall see. More than 190 countries committing themselves to controlling their greenhouse gas emissions is a positive historic event, whatever the doubts and misgivings for much that remains to be done to limit the negative impacts that climate change is having on our societies.

But what does the Paris Agreement call for? First of all, the agreement is built around three main objectives:

- limiting the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C, as this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts due to climate change;

- increasing the capacity to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change, promoting resilience and adaptation investments in developing countries, in particular to reduce threats to food production;

- making adequate financial resources available to support a climate-resilient and low-carbon economic development.

To achieve each of these objectives, the document outlines a range of measures, which will guide the actions of countries from 2020 onwards. In particular, for the objective of limiting the increase in temperature below the 2°C safety threshold set by the scientific community, the Paris Agreement aims at:

- achieving a peak of global emissions of greenhouse gases as soon as possible and then bringing about a rapid reduction until, in the second half of the century, a parity is achieved between emissions produced and those absorbed. One tool for reaching these objectives are the “intended nationally determined contributions”: mitigation efforts that are progressive over time and that all UNFCCC Party Countries are called on to undertake and communicate;

- providing support and flexibility for developing countries, which may need more time before achieving a trend of decreasing emissions, and whose need for financial and technological support for the implementation of these commitments is recognized in different parts of the text;

- assigning to developed countries a leading role in mitigation action through absolute targets for reducing domestic emissions, while developing countries will be able to increase their emissions, though reducing them to what they would have been without the adoption of their INDCs, and being encouraged to eventually undertake broader reduction targets;

- asking each country to update its national contributions every five years, by providing all the information needed to ensure clarity and transparency. Cooperation mechanisms, including market mechanisms to lower implementation costs, may be undertaken voluntarily by countries, if this serves to increase the ambition of the action and if environmental integrity is respected.

In addition to mitigation, important recognition is given to the role of adaptation, since even if the limit of 2°C was observed, some of the impacts of climate change will be unavoidable. In general, the Paris Agreement defines adaptation as a multi-level global challenge, from local to international, as well as a key component of the response to climate change in the long term. For this reason, the Paris agreement:

- recognizes the need for adaptation of developing countries and the consequent efforts to meet them, along with the need to strengthen international cooperation in favor of the most vulnerable countries;

- encourages all countries to implement measures and adaptation plans, both nationally and cooperatively, and to communicate and update them periodically as part of their national contributions;

- commits developed countries to implementing measures of technological cooperation and transfer of technology in favor of developing countries in order to help them cope with the by now inevitable impacts of climate change.

Nevertheless, the Paris Agreement stipulates that the developed countries should continue to provide financial support to developing countries, on an increasing scale and through a wide variety of sources and methods. Information on this support, its scope and layout, is to be communicated by each country every two years. Special attention should be given to communicating the contribution made by national public funds, even though support from other countries or private stakeholders is still encouraged. As with much of the Agreement, additional guidance is furnished by the implementing provisions, which, in this case, state that before 2025 governments will have to establish a new collective financial commitment and that the starting point will be the amount determined by the previous negotiations for 2020, namely 100 billion dollars per year.

Lastly, a crucial point is the review process of the agreement’s implementation, which will be set up starting in 2023 and repeated subsequently every 5 years in order to assess progress in collectively achieving the long-term objectives. The review will cover all the key elements of the Paris Agreement: first, an assessment of national contributions to mitigation, but also adaptation actions, financial commitments, even in the light of future scientific results provided by the IPCC. The results of this process will be used to inform and update subsequent national contributions and the actions that the parties will be called on to provide. Taking into account the concerns of those countries that believed this date to be too far off in time, especially in light of the analysis of the mitigation commitments, an initial assessment will be made as early as 2018, intended however as an informative dialogue for outlining the next national contributions.

From a legal perspective, the Paris Agreement has formalized a new approach consisting on the one hand of a legally binding part that establishes common rules to promote a transparent process and to ensure an assessment of its objectives, supported by elements left to the national legislation of each State, for example the INDCs. This “hybrid” solution was dictated by the need to obtain a large consensus on the final document and thus provide a tool that is receivable in national legislations without much difficulty. The rigid distinction included in the Kyoto Protocol, among Annex I states, with binding reduction commitments as opposed to non-Annex I states, which had none, has been replaced by a new more nuanced and flexible form of differentiation that simply distinguishes developed countries from developing countries. Many provisions establish common rules and commitments, yet allow respect for the different national circumstances and capabilities of the poorer countries, through both the so-called “self-differentiation” implicitly included in the national contributions, and more detailed rules, as in the case of financial support.

The Paris Agreement has learned from past mistakes and has tried to respond to the urgency for climate action by encouraging the widest possible participation (even though giving up some elements that would increase its effectiveness). From this point of view, the agreement can certainly be considered a success.

Although more than 190 countries have indicated their national contributions, making up more than 98% of global emissions, they are not yet sufficient to limit a temperature rise to below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels. Starting with the UNFCCC itself, several studies have evaluated the aggregate effect of the Paris agreement, stressing that further reductions will be needed after 2030, otherwise the temperature increase at the end of the century will be closer to 3°C than to 2°C. Much will depend on what the countries will be able to accomplish after 2030. If emissions decline rapidly and if we acquire technologies capable of removing CO2 from the atmosphere on a large scale, then the 2°C target will be achieved. Otherwise we will have to adapt to a very different climate from what we have now.

It is obvious that the more we postpone significant emission reductions, the more ambitious they will have to be in the future. For this reason, the review and update process on the commitments outlined in the Paris Agreement will play a key role in promoting increasingly ambitious actions.

Likewise, the mobilization of financial resources to enable developing countries to implement mitigation and adaptation plans, as well as those that all countries will invest in research, development and transfer of new technologies, will be crucial for achieving the goals that have been set.

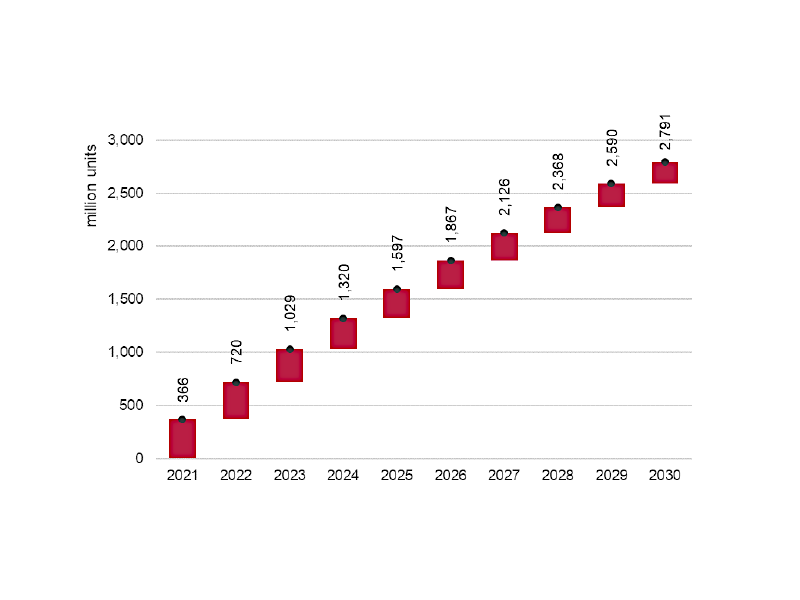

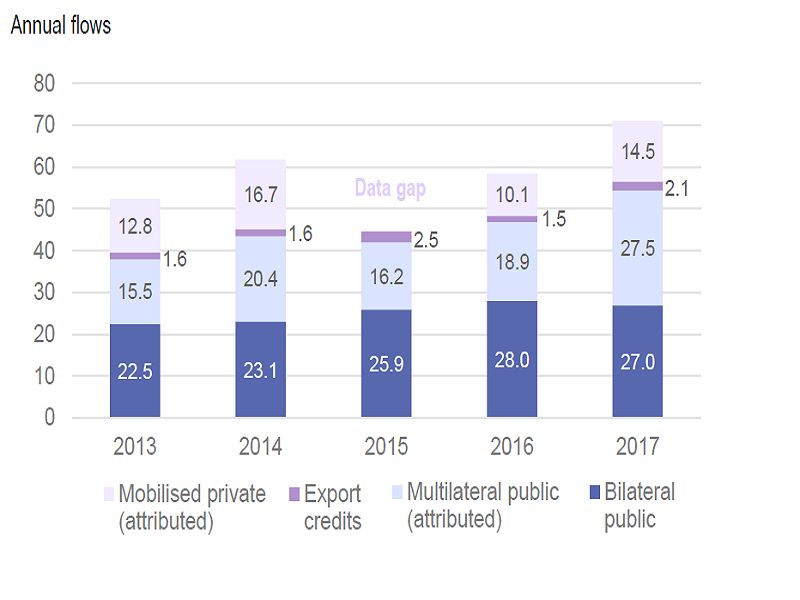

A recent study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), shows that in 2017 the developed countries provided 71.2 billion US dollars to developing countries, 75% of which came from public funds (see barpolt). Just as significant is the fact that the number has grown in recent years, because of both the increasing commitment of governments and increasingly transparent reporting systems. However, the figure is still far from the needs of the developing world, estimated by the World Bank as 140-175 billion dollars a year by 2030 for mitigation actions and another 75-100 billion for adaptation.

Source: OECD 2019

Overall, the Paris Agreement is an important step in the right direction. A realistic step, which will enable governments to work together within a robust process of review and growth in commitments. The Paris conference has therefore closed one cycle, that of the Kyoto Protocol, and opened up another, larger one in terms of participation based on past achievements, but open to future improvements. It is now up to the individual countries to adopt concrete mitigation and adaptation measures. In particular, there are some very important decisions to be taken urgently:

- Investing significant resources, quadrupling those invested today, in research and development of low-carbon technologies, especially for producing electricity and for its use and storage. Research and development of technologies for CO2 removal from the atmosphere, to reduce energy and water poverty, for developing climate-resistant seed, and for low-cost dissemination of education programs throughout the world.

- Taking steps to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels, starting with coal, which should be eliminated at least in all the industrialized countries, and replaced by gas.

- Promoting the replacement of fossil fuels with renewable energy by eliminating subsidies to the former and using the financial resources so obtained to fund research on the latter.

- Taking measures to make sure that every ton of carbon emitted has a price that will encourage technological innovation, energy efficiency and the gradual replacement of fossil fuels with renewable energies.

Thus, we need far-sighted public and private investment decisions. In Paris one important role was played by the private sector, which for the first time has made important commitments to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. More generally, one key success of COP 21 was also the mobilization of the civil society and local institutions: the mayors of major cities, private companies, activity and research networks, and the actions of many NGOs are showing how change is possible and above all an opportunity.

Why are climate policies important?

5/06/2020

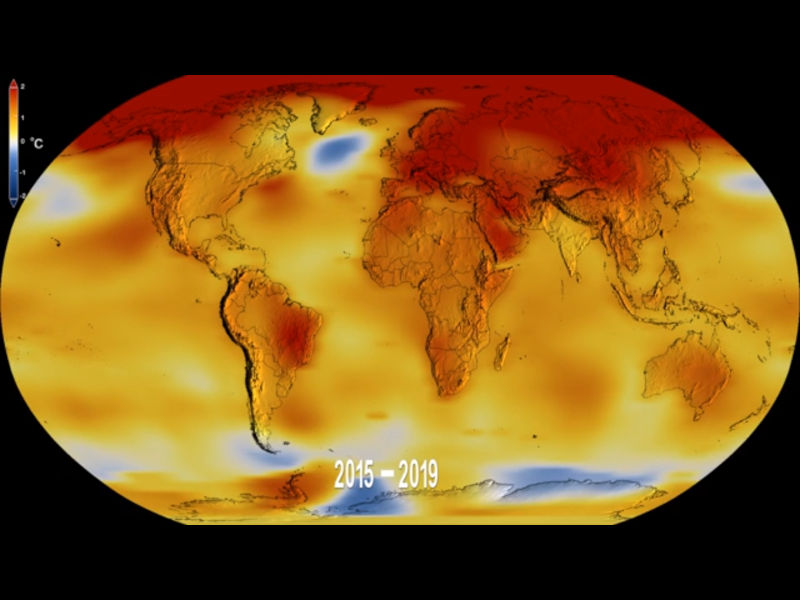

Temperature increase in the last 100 years was about 0.8°C (IPCC, 2014). The last decade was the warmest decade on record, with the past five years being the warmest of the last 140 years.

Earth’s global surface temperature in 2019 was the second warmest since modern record-keeping began in 1880, and 0.98°C (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 1951-1980 mean, according to NASA (see the NASA video about "Global Temperature Anomalies from 1880 to 2019"). Overall, 2019 temperatures were second only to those registered in 2016.

Studies based on historical data demonstrate that changes in climate variables influence social and economic outcomes in many sectors and contexts, including mortality, assets’ loss, agriculture, labour productivity, electricity, aggregate economic indicators migration, but also aggression, violence, and conflict (Carleton and Hsiang, 2016)

To avoid dangerous impacts of climate change, urgent policies are needed to drastically cut GHG emissions in the next decades. Although there is broad evidence of the overall co-benefits associated with strong and early mitigation actions and of the fact that they will outweigh the costs, governments need to promote comprehensive policies able to reduce emissions at the lowest possible cost. This is why putting a price on carbon emissions is a key component of national efforts to tackle climate change. Carbon pricing policies include market-based instruments, accompanied by better integration of climate change objectives across relevant policy areas such as energy, transport, building, agriculture or forestry, and other measures to speed technological innovation.

Since the early 1990s the European governments and other developed countries have adopted national programmes aimed at reducing emissions. To coordinate the efforts at the international level, world leaders meet every year within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), where they adopted the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and, at the end of 2015, the Paris Agreement.

The Paris Agreement affirms the urgency to tackle climate change and foster a climate-resilient and inclusive low-carbon development. The pledge-and-review approach launched by the Agreement requires more than 190 States to periodically update their climate plans toward more and more ambitious actions. This provides an unprecedented opportunity to learn about domestic priorities on climate change policy. At the same time, it calls for new systematic tools to track countries’ commitment toward the achievement of global objectives (i.e. limiting the average temperature increase well below 2°C) as well as for a comparison, which considers synergies and adverse impacts arising from national specificities.

Falling at the intersection of public policy, climate change economics and climate science, my Marie Skłodowska Curie project, ACTION, will develop a quantitative approach to empirically evaluate national climate policies in terms of stringency, determinants, and economic impacts. The new evidence provided will enhance transparency and comparability among countries’ climate efforts and offer useful insights into a fair and just transition toward the sustainable development. By assessing the effectiveness of current measures and by identifying successful elements and obstacles, ACTION will support the EU and its Member States to better design their future climate agenda. Research findings will contribute directly to the achievement of the climate change objectives laid out in the EU 2030 Climate & Energy Framework. Moreover, understanding policy stringency and its socioeconomic dynamics in other countries will facilitate the EU to integrate its climate strategy in a wider context, and to play a leading international role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

A brief overview of the project

Credit: WRI 2020

27/05/2020

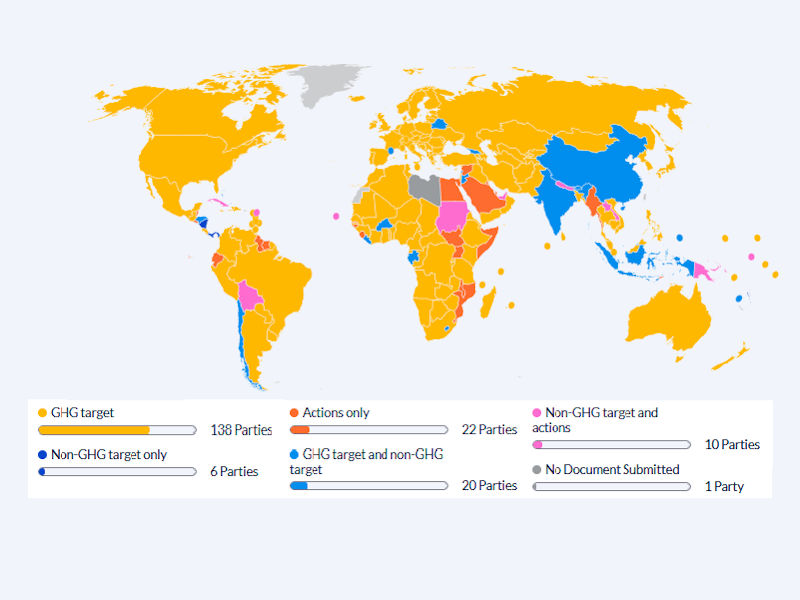

The 2015 Paris Agreement is a key step towards strengthening a global response to address the threat of climate change. It sets global objectives that all signatory countries have to contribute to achieve through the implementation of urgent actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote climate-resilience and low-carbon development. The new bottom-up approach launched in Paris and the large heterogeneity of the contributions (see map) presented saw increased academic attention on how the different types of national targets proposed can be evaluated and compared.

ACTION – Assessing Climate TransItion OptioNs: policy vs impacts – aims at enhancing transparency and comparability among countries’ climate change policies while offering insights into a fair and just transition toward the sustainable development. The project will develop a quantitative approach to empirically assess national climate policies in terms of severity, drivers and economic impacts.

The overarching objective of ACTION is twofold:

- enhance transparency and comparability of climate change measures at different levels while clarifying factors determining policy ambition;

- provide evidence on the equitable transition toward a low-carbon and sustainable development.

To achieve these goals, the following specific objectives will be pursued:

- Provide a cross-country analysis of climate policy stringency over time:

- Create a database of climate change policy measures adopted over the years by countries;

- Develop and apply a flexible and replicable set of indicators to assess stringency of existing climate policy measures and to rank countries’ performance.

- 2. Provide evidence of international and national factors influencing climate policy adoption and effectiveness:

- Investigate the specific role of the process leading to adoption of the Paris Agreement on the level of stringency of national climate policy:

- Empirically investigate the effects of environmental, social, economic and political factors (e.g. institutions, education, economy, political orientation, lobbying, etc.) on individual countries’ policy stringency and emission change for the period considered.

- Provide evidence of the comparative effect of climate policy stringency and climate change impacts on inclusive economic development:

- Quantify the simultaneous effect of the climate policy stringency indicator and other climate change-related variables (e.g. temperature and precipitation variations, damages induced by climate/natural extreme events) on growth, inequality and poverty.

The project will exploit the recent increase in availability of climate policy information, both in terms of geographic and temporal coverage, to significantly advance the empirical literature on climate policy evaluation and comparison. The development of a systematic measure to evaluate climate and clean-energy policy stringency will allow not only to consolidate the analytical approach to assess countries’ performance but also to move the understanding of underpinning factors a substantial step forward. Considering the combined effect of policy and impacts on economic development will represent an unprecedented effort toward the assessment of the overall pressure climate change is imposing on our society.

About

ACTION – Assessing Climate TransItion OptioNs: policy vs impacts – aims at enhancing transparency and comparability among countries’ climate change policies while offering insights into a fair and just transition toward the sustainable development.

The project will develop a quantitative approach to empirically assess national climate policies in terms of severity, drivers and economic impacts. Project results will assist policymakers in understanding the effectiveness of coordinated policy efforts and design their future climate agenda. ACTION will be hosted in two highly qualified institutions: during the outgoing phase (24 months) at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, under the guidance of prof. Aldy, and during the incoming phase (12 months) at the Department of Economics of Ca’ Foscari University. The supervisor of the project is prof. Enrica De Cian.